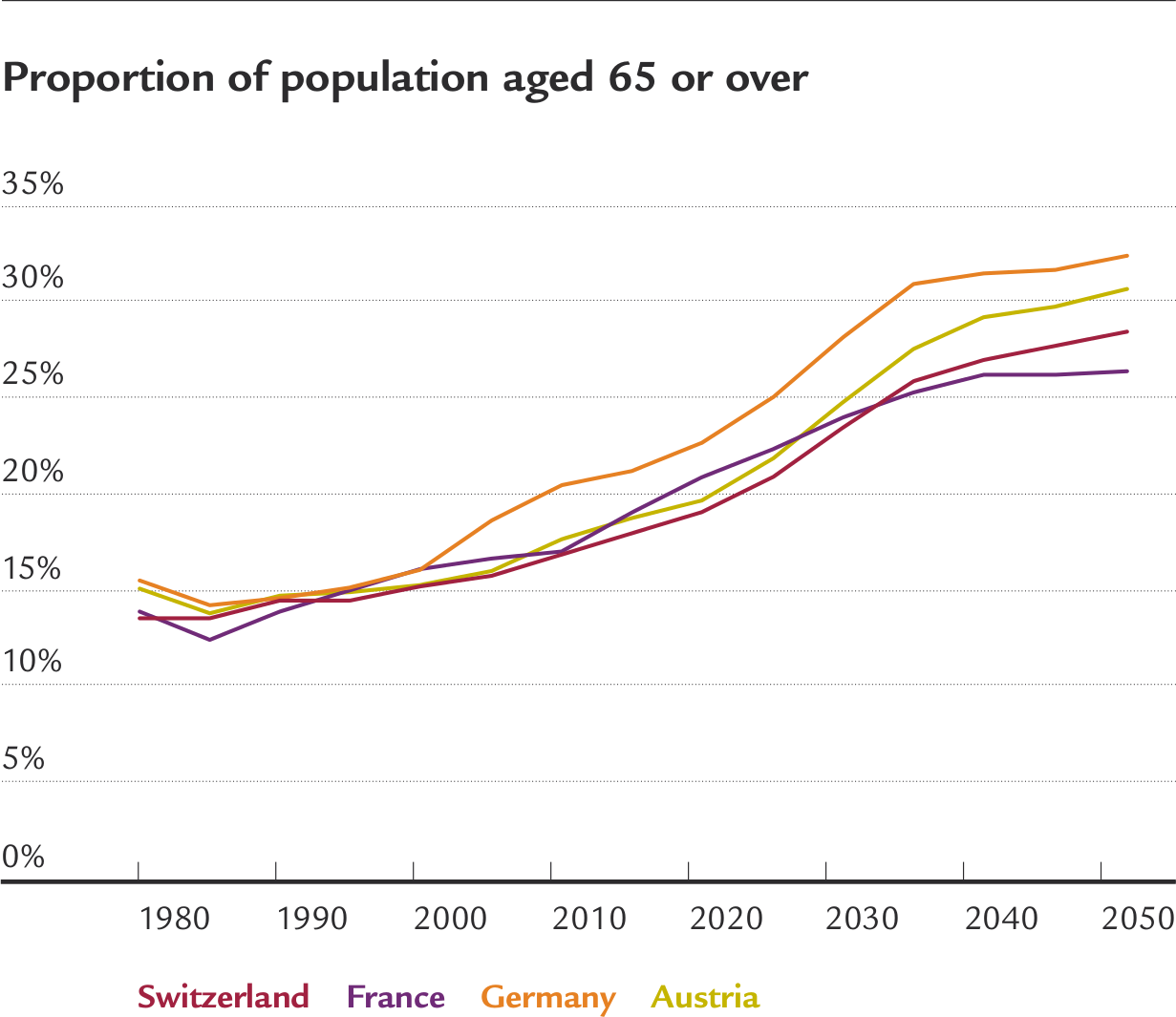

- Europe is at the forefront of a longevity revolution. Currently about one in five citizens in Switzerland, Germany, Austria and France are aged over 65. By 2030 this will have risen to roughly one in four.

- The Economist Intelligence Unit, sponsored by Swiss Life, conducted a survey of over 1,200 residents of Germany, France, Austria and Switzerland. It shows that longevity is frequently viewed negatively, despite the array of individual and social benefits that this development presents.

- Much of Europe is ill prepared to address the challenges of ageing populations, and the survey indicates that significant majorities of people reaching retirement age are unlikely to seek to continue their professional lives.

- Support for individual autonomy and strong social connections are vital to realising the potential offered by a longer lifespan.

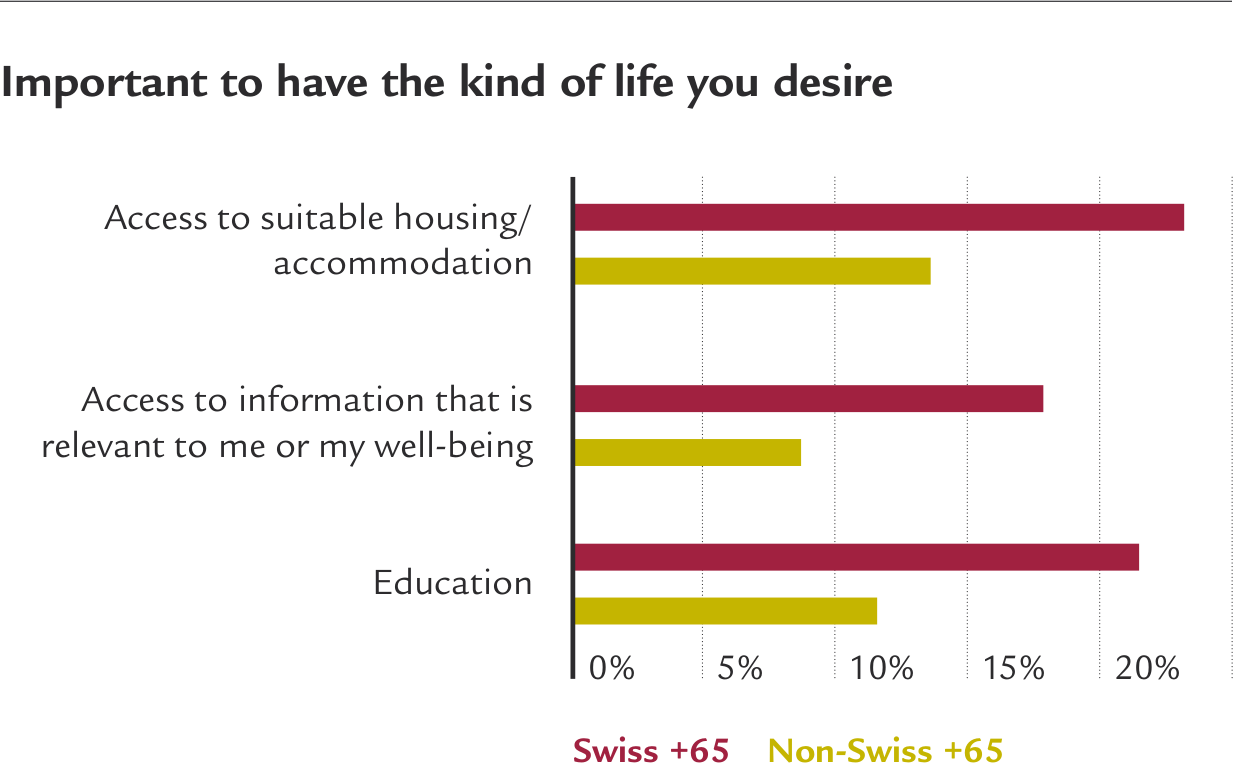

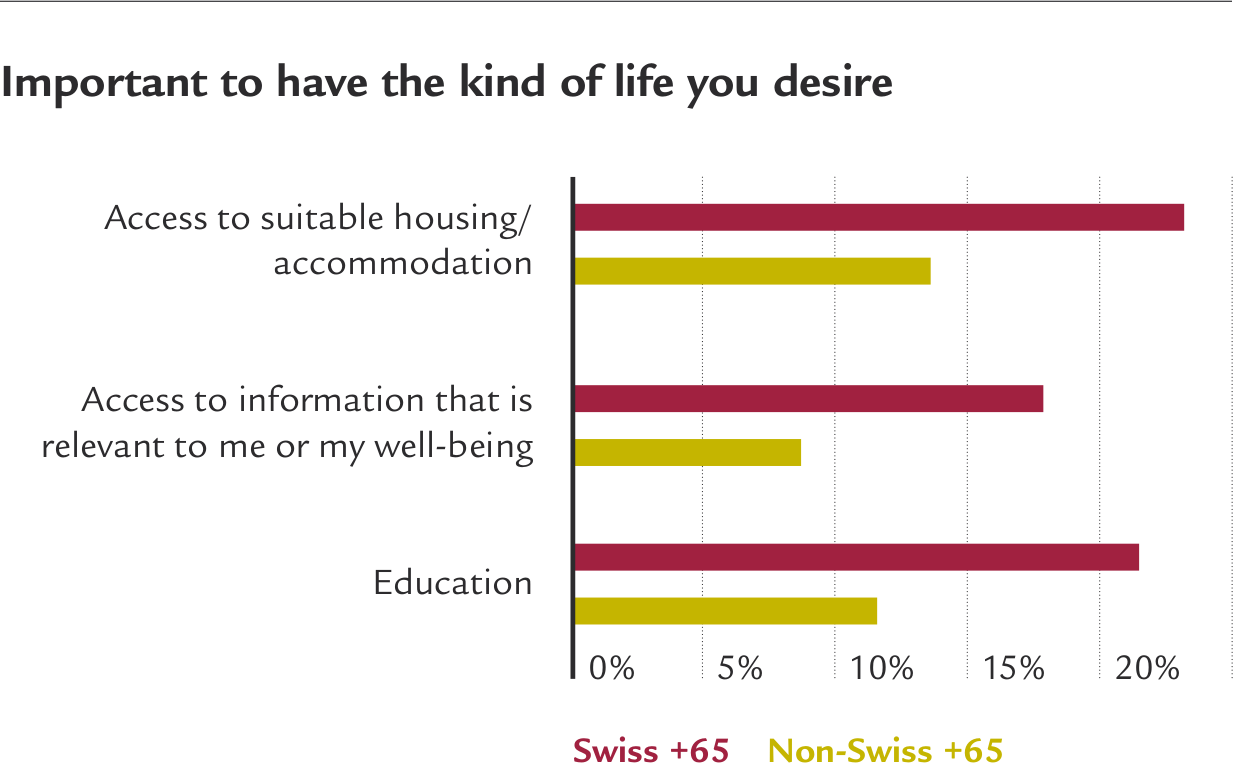

- In terms of what aspects of life senior citizens want to have sufficient control after their retirement, Swiss seniors are more likely to focus on education and access to information than their peers in neighbouring Germany, Austria or France.

The markedly longer lifespans of European citizens bring opportunities as well as challenges. To investigate these issues The Economist Intelligence Unit conducted a survey of more than 1,200 residents of Germany, France, Austria and Switzerland. The conclusions drawn from the findings of the survey are that that longevity is frequently viewed negatively, despite the array of individual and social benefits that this development presents.

Causes for concern

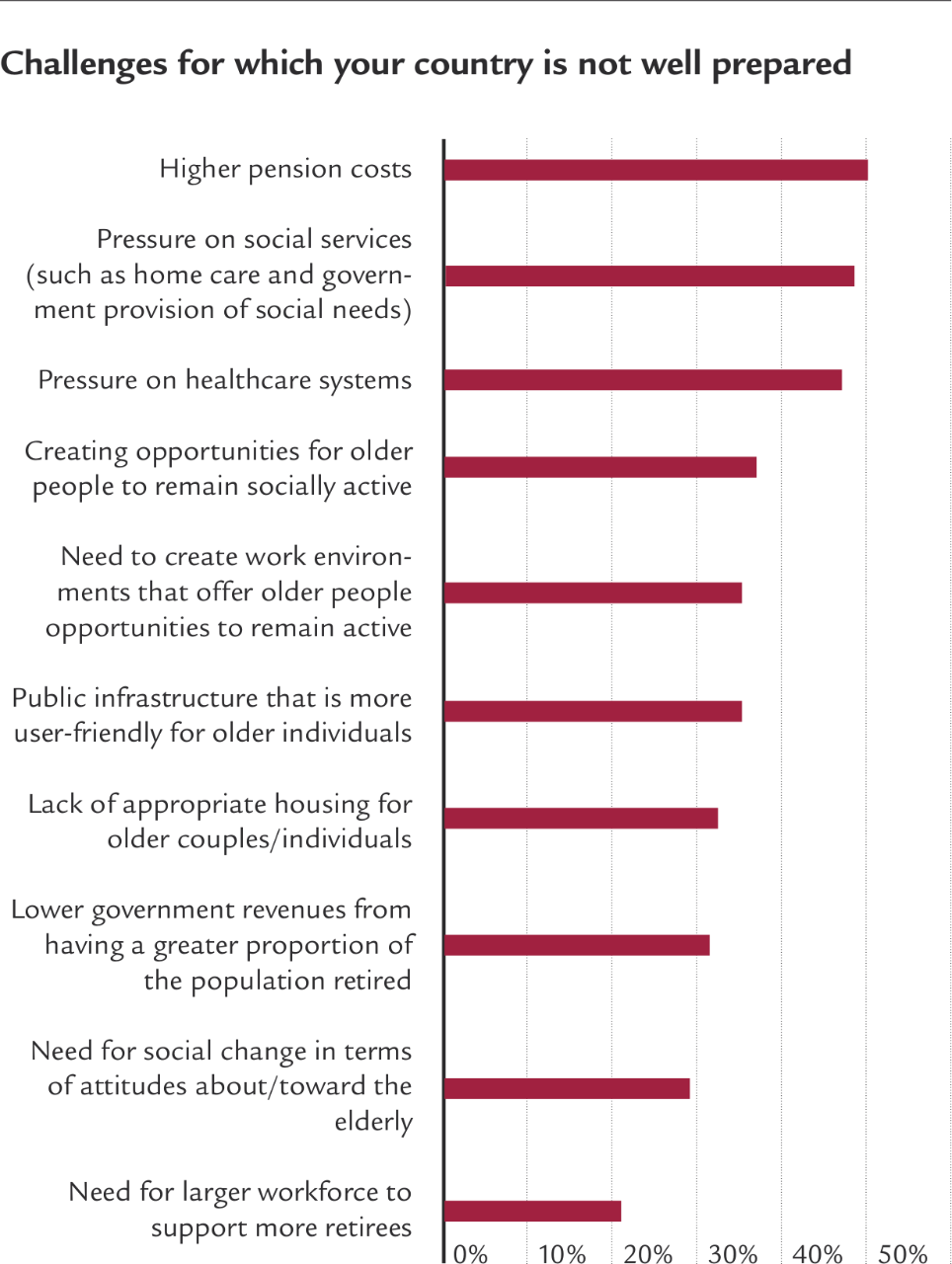

A substantial number of respondents believe that their countries are ill prepared for the challenges of an ageing population. Older populations bring inevitable changes in societal needs. Our survey shows that a significant percentage of respondents are concerned that their countries are not ready to address these challenges, and 29% believe that even basic attitudes towards the elderly need to change. The most commonly cited issues, though, surround areas in which governments play a dominant role: 47% of those surveyed in Germany, France, Austria and Switzerland say that their countries are not well prepared for the pressure on healthcare systems that an older population will bring; 48% say the same of social services; and fully half believe that their governments are not ready for the higher pension costs that are coming. But many of these concerns could actually be better addressed by supporting seniors to maintain healthy lifestyles and to continue working later into their lives.

Longevity: problem or opportunity?

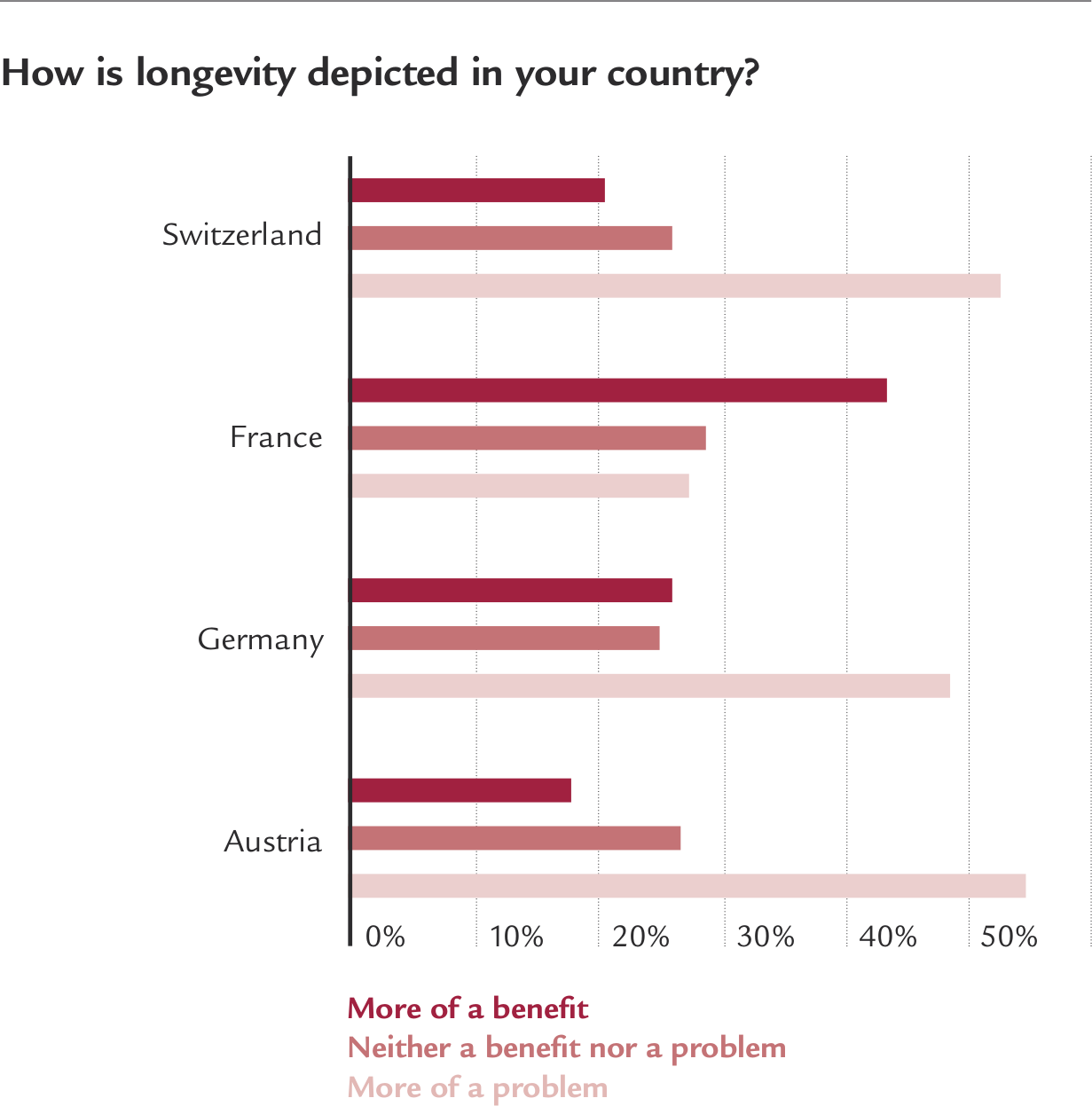

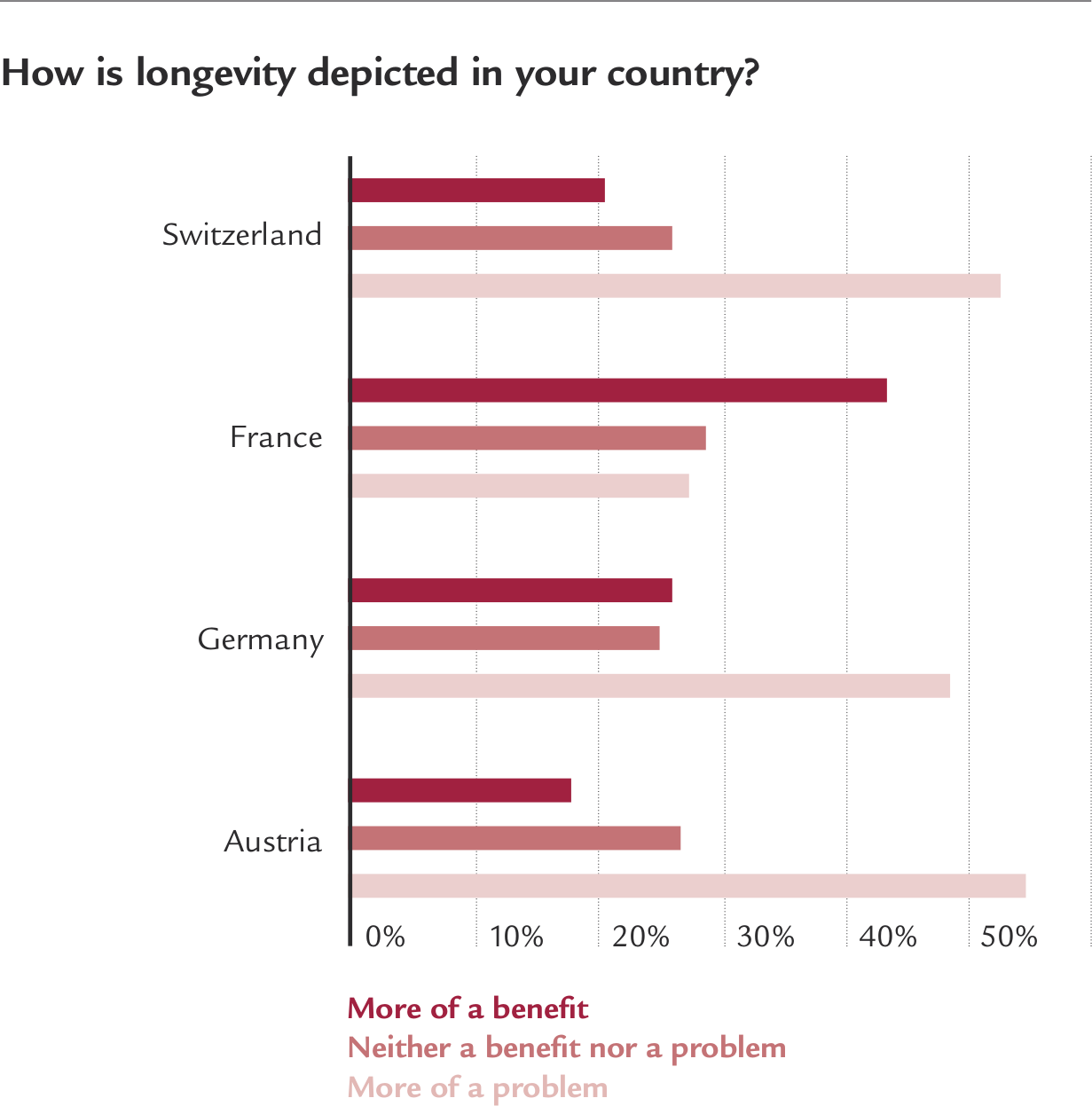

Despite an array of personal and societal benefits, increased longevity is more often portrayed as a problem than an opportunity in Austria, Germany and Switzerland. Overall, survey respondents are more likely to say that greater longevity is seen negatively in their country rather than positively: 42% report that it is depicted as either a significant source of problems for society or as more of a problem than a benefit; only 31% believe the opposite is true. These average figures, though, obscure significant national differences. In France, the majority (43%) of respondents assert that longevity is generally depicted as a benefit to society or more of a benefit than a problem, against just 28% who say that it is seen in a negative light. In the other three countries, the reverse is true. The equivalent figures, on average, are 23% who say that longevity is depicted positively, while 51% feel that it is seen as a negative development.

The vital importance of independent living

Individuals place an extremely high value on living independent, self-directed lives when older. In considering the issues of autonomy and longevity, an overwhelming majority of survey respondents say that continuing independence is extremely (73%) or very (18%) important to them personally. Substantial consensus also exists on the main requirements for this independence: 78% list physical health as one of the three key requirements to having the level of control over their lives that they wish, and 73% say the same of mental health. Less frequently cited in this regard, but still the third most common choice, is a sufficiency of economic resources. The younger generation of those surveyed is more likely to be focused on money (58%) than respondents already over 65 (47%). This may reflect the fact that the younger generation is still setting aside earnings for private pensions and other savings.

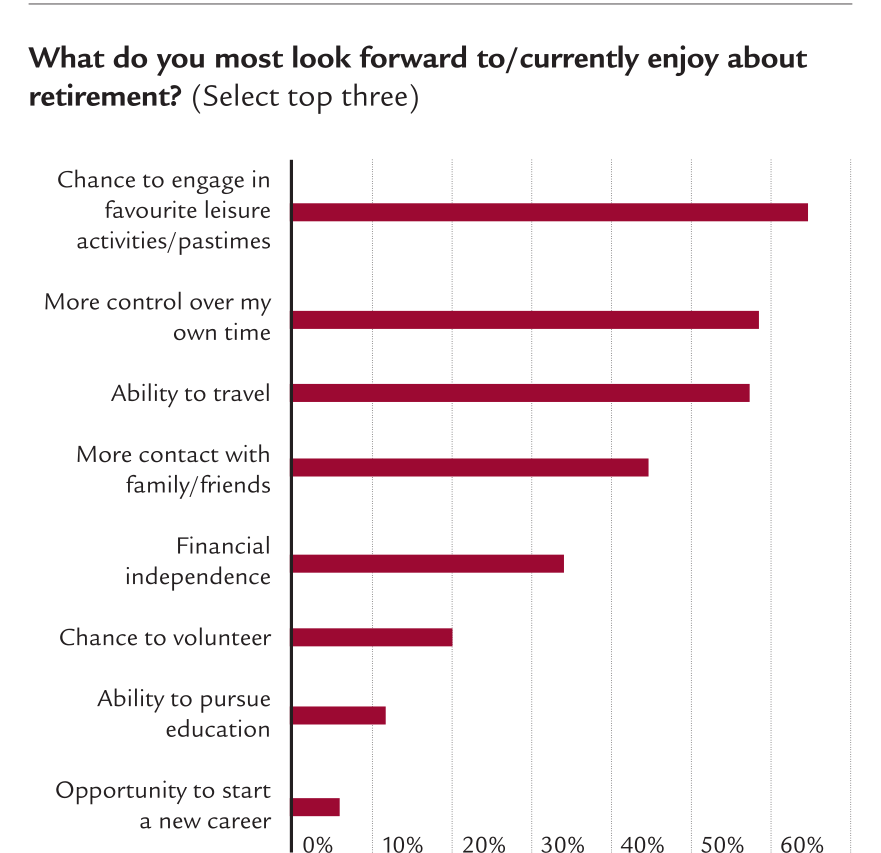

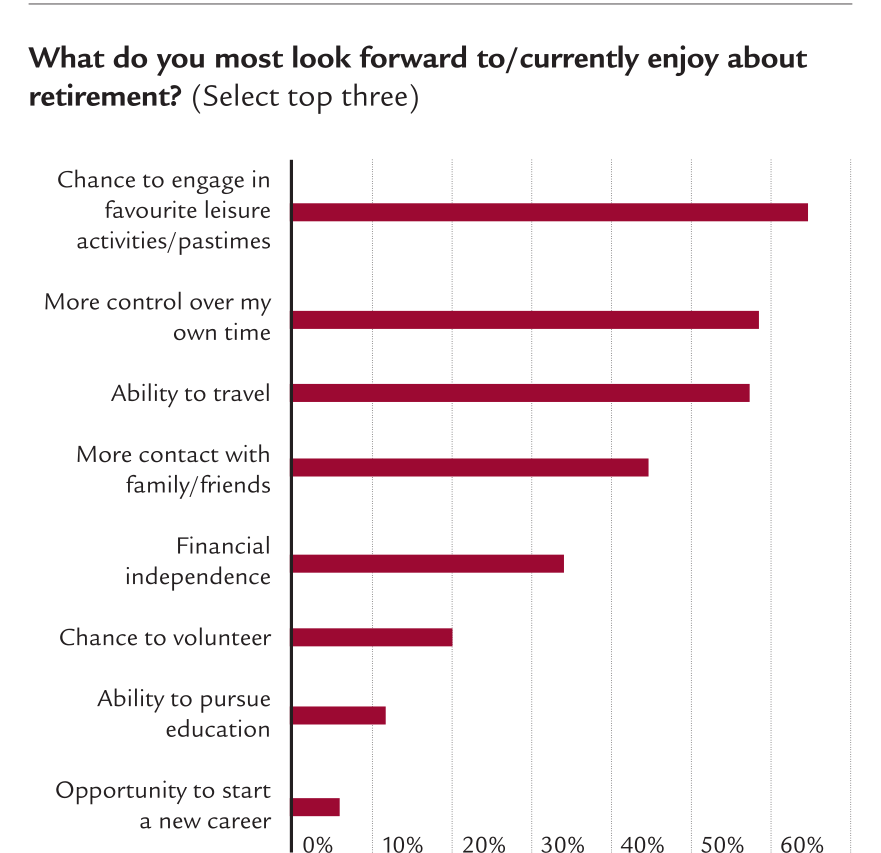

The way in which individuals are spending, or wish to spend, their later years also reflects their desire for independent living, enjoyed in good health. When asked what they currently enjoy the most, or look forward to, in these years, 65% say the chance to engage in favourite leisure activities and pastimes; 58% cite greater independence (“more control over my own time”); and 58% opt for the ability to travel. These are not merely individual gains: a majority (51%) highlight greater opportunities for leisure as one of the top benefits of increased longevity to society as a whole.

Social connections are key

Independence does not mean isolation: social connectedness is an important part of how individuals envisage their later years. Although respondents wish to maintain control over how they live when older, many highlight the social and individual benefits gained as a result of greater longevity. In particular, 53% of those surveyed believe that deeper, extended family connections will result from the fact that more generations are alive at the same time and that their lives overlap for a larger number of years. This, in effect, is cited as the most significant benefit to society as a result of greater longevity. Similarly, the third most cited social gain is a strengthening of civil society as older individuals are more likely to volunteer and be politically active (46%). In France these views are particularly pronounced, with 60% seeing deeper family connections as a leading social benefit from longevity and 50% saying the same of a strengthened civil society.

This positive attitude towards social connectedness also reveals itself in respondents’ answers when questioned about their own lives. For example, only 20% see an ability to make choices independent of the preferences of others, in particular of family members, as a key prerequisite for their own independence. Indeed, for self-determined lives, autonomy and social connections are interlinked, not opposing goals. Accordingly, 44% of respondents consider the chance to have more contact with family and friends as one of the top personal benefits from a longer life, while 37% report consciously cultivating close relationships as a way to be able to live a life of their own choosing in later years—the most common strategy in pursuit of this goal after pursuing a healthy lifestyle (74%) and making investments (45%).

Swiss exceptions

Switzerland pulls away from the other countries surveyed in intriguing ways. When considering the areas of their lives they need to be able to control in order to lead a fulfilling life in their later years, Swiss respondents focus primarily on issues of health (mental and physical) and economic resources, much like their peers in neighbouring countries. But they are noticeably less likely to emphasise these areas than respondents in Austria, Germany and France, as their focus has shifted more towards education and access to information. This is particularly the case among respondents over the age of 65. Given Switzerland’s higher level of GDP per capita and lower levels of chronic disease, it is possible that many respondents have moved from physical and financial security towards self-actualising goals. However, a secure quality of life does not come without its price—indeed, the counterpoint to Switzerland’s comparatively high incomes is the high cost of living. This is evident in the case of housing, as Swiss respondents are far more likely to cite concerns about access to housing than their peers in the other three countries surveyed (24% vs 13%).

Living to work?

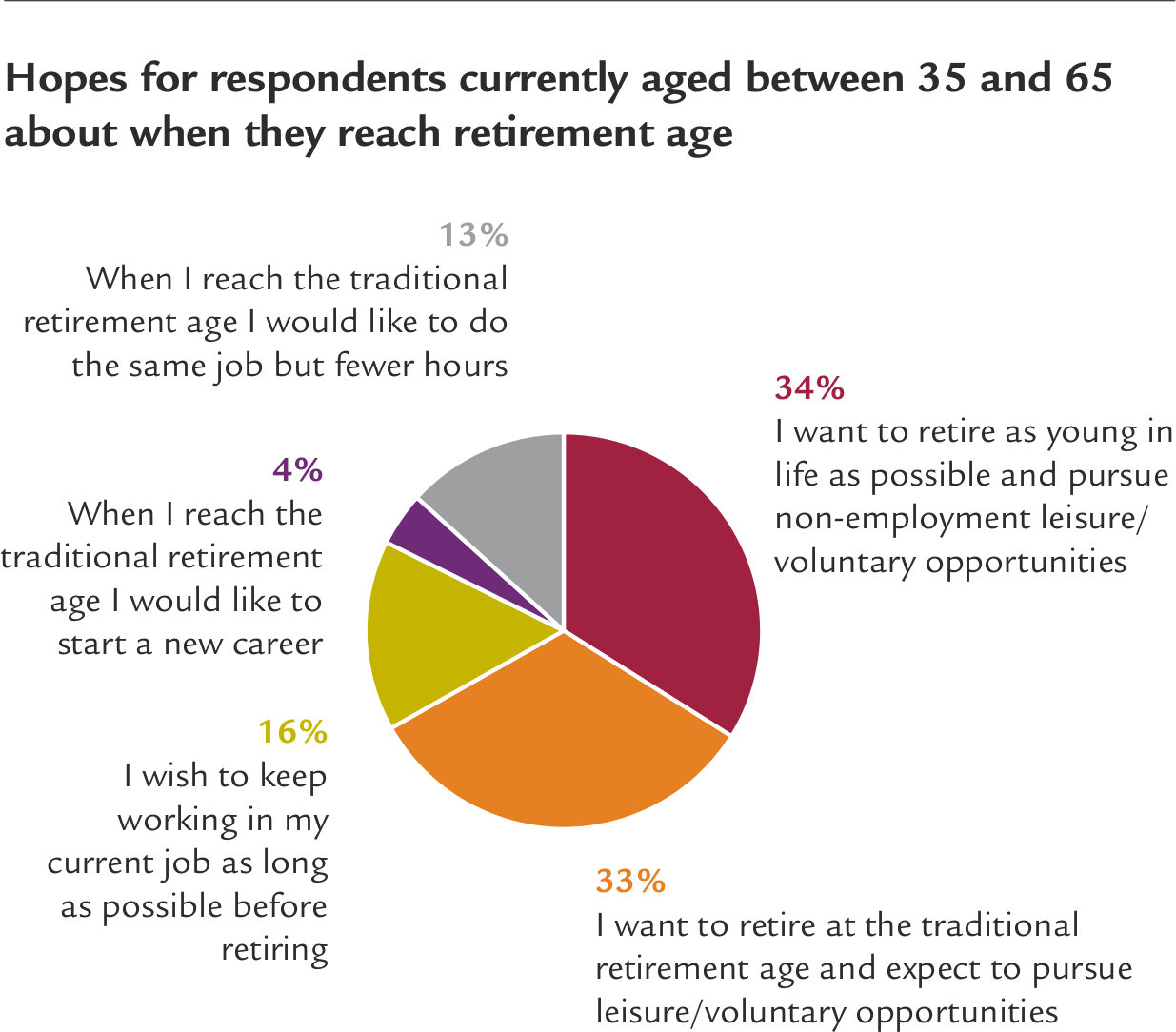

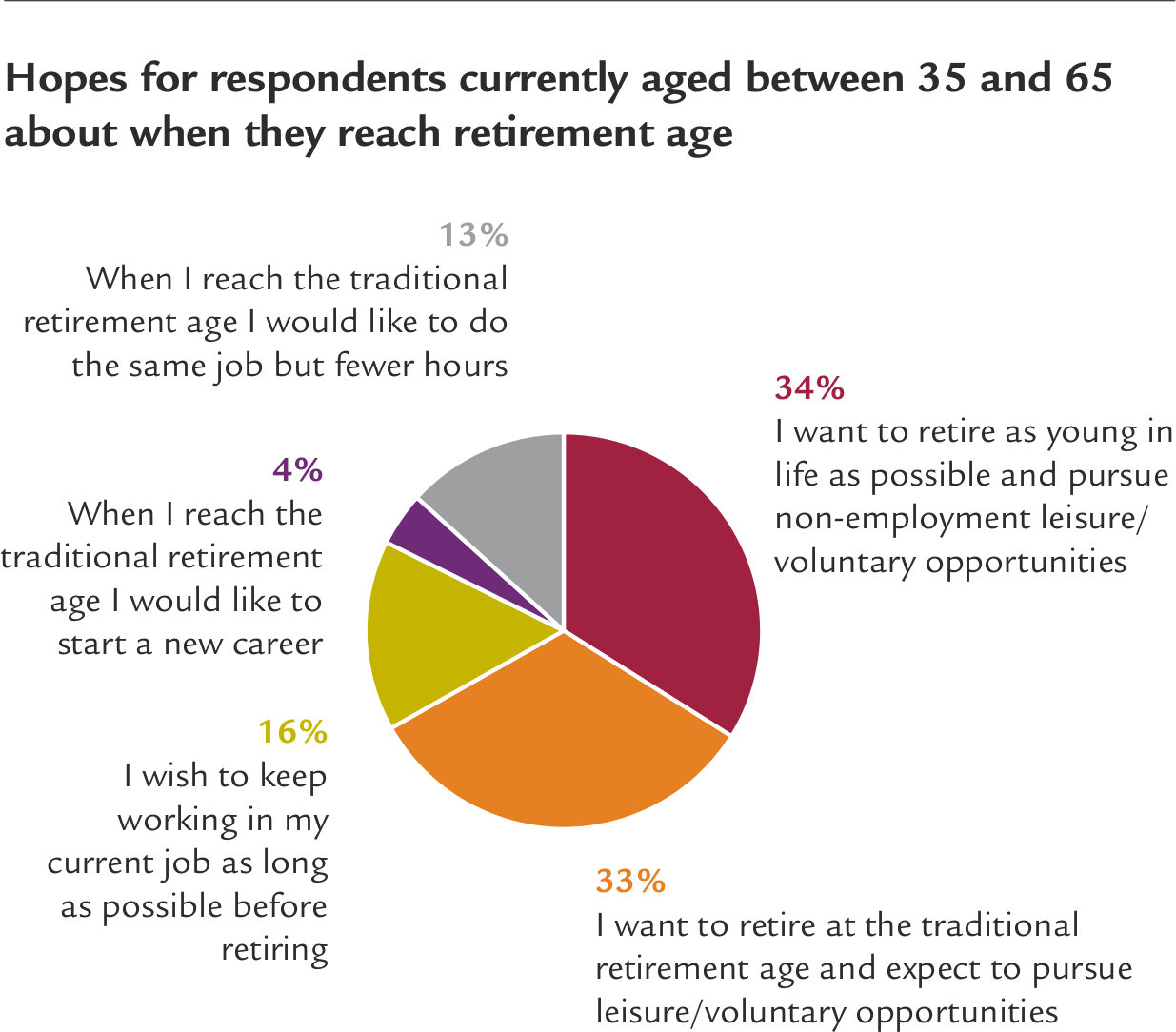

Paid employment past the traditional retirement age remains a minority interest. In the four countries in the survey, currently only a small minority of those aged over 65 work: even among those aged 65-69, labour-force participation rates range from 5.9% in France to 22.4% in Switzerland. The survey results indicate that the majority of the population in these four countries is unlikely to choose continued employment if it can be avoided. Among respondents who are already 65 or over, 55% report that they wanted to stop working at or before the traditional retirement age. Among the survey’s younger group, the number wishing to do so reaches 67%.

Of the respondents currently under 65, only 4% want to start a new career upon retirement, but 16% say that they would like to keep their job past the traditional retirement age. A further 13% would continue in the same role if they could work fewer hours. Taken together, one-third could be enticed to remain in the workforce if the conditions were right—far above current levels. Indeed, for those already over 65, this rises to 45%. Younger individuals may follow their older peers as the prospect of retirement becomes more imminent. This indicates that policymakers seeking to increase workforce participation later in life have a substantial number of individuals who currently fall out of employment but could be successfully encouraged to stay on given the right conditions.

An unappreciated workforce

The current mindset may be a challenge as employers do not seem to see older workers as valued employees whom they wish to retain. Although Europe has seen intense debates about retirement ages, the EIU survey suggests that conditions are not encouraging extended careers. Only 27% of respondents report that in their current jobs—or their last place of employment in the case of unemployed workers and retirees— all levels of seniority in the company respect the experience of older workers. For 22%, the situation goes far beyond lack of respect: the input of older workers is simply marginalised. These figures are almost identical for younger respondents (mostly still in work) and seniors (generally retired), suggesting no recent improvement in employer attitudes.

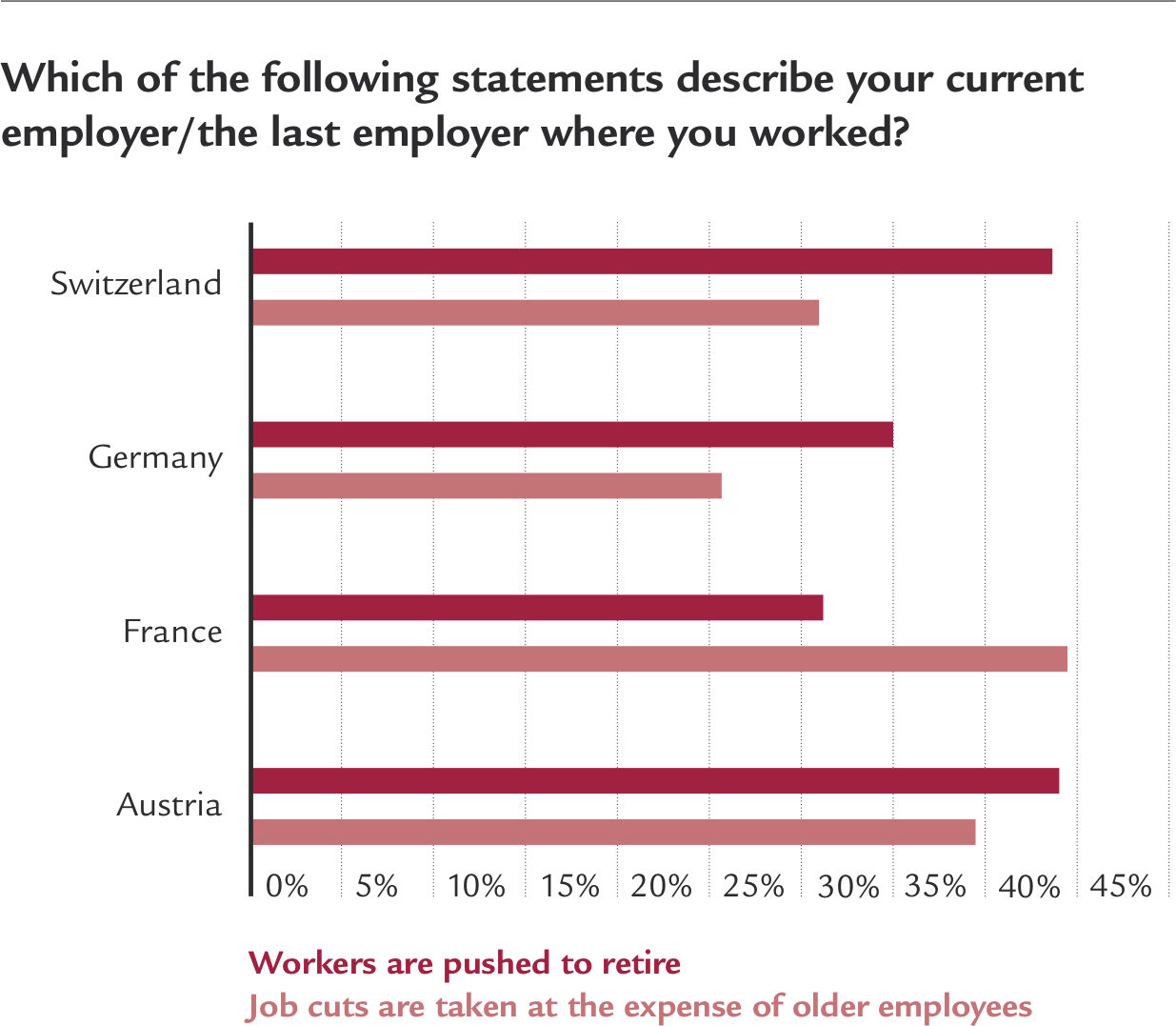

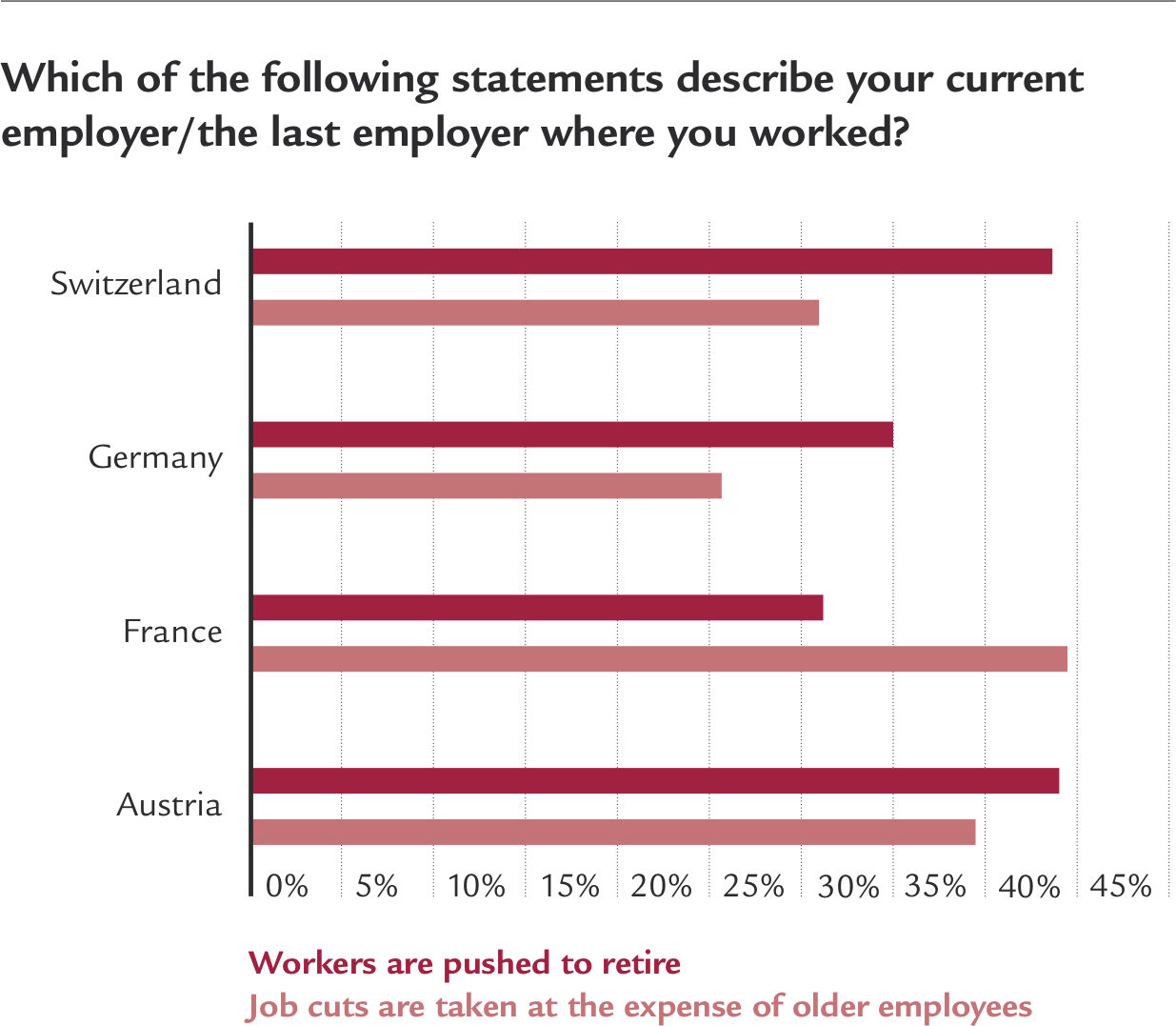

Not surprisingly, creating a workplace environment that allows older employees to thrive is rare: only 10% of respondents report that their current or last employer has effective policies for getting the most from such workers. Far more are seen as actually targeting the old, with 36% of respondents—and up to 44% in Austria and Switzerland—saying that jobs cuts at their workplace target older employees, while 35%—rising to 44% in France—say that older workers are being pushed to retire.

Paying the piper

National perceptions differ significantly over who should pick up the bill. Pensions and services directed at the elderly cost money. When asked who should be primarily responsible for the costs of retirement in societies faced with increasing longevity, respondents are split along national lines. In Austria and Germany, the most common answer is government (85% and 76% respectively), with individuals next, albeit a substantial distance behind (47% and 45%). In France and Switzerland, on the other hand, individual retirees are more likely to be seen as being responsible (61% and 63% respectively), although in both countries almost as many select the government (59% and 61%), suggesting that people feel the onus is a collective one. Clearly Europe’s societies need to open a balanced conversation about the responsibilities and opportunities that greater longevity presents in order to address its challenges and embrace its benefits.

About the survey

The survey, conducted in December 2015 and January 2016, polled 1,265 people in Austria (16% of the total), France (36%), Germany (39%) and Switzerland (9%). The group was split roughly evenly between those aged between 35 and 65 (52%) and those over 65 (48%), as well as between men (53%) and women (47%). The group was also drawn largely from the middle of the economic spectrum, with 68% of respondents estimating that they fell between the 25th and 75th percentiles of income in their respective countries.

Written by

![Little Old Lady with her Pets enjoying Summer on the Balcony.

Please see more similar images here:[url=http://www.istockphoto.com/file_search.php?action=file&lightboxID=8234435]

[img]http://s700.photobucket.com/albums/ww8/bi_bi/lightboxes/lifestyle.jpg[/img][/url]](/content/internet/com/en/home/blog/stadtentwicklung-demografischer-wandel/_jcr_content/moodimagearticle/image.1558701378981.transform/16_9_3840w/Seniors_are_going_to_town.jpg)