- Housing can impair or enhance one’s quality of life and sense of autonomy.

- To ensure autonomous and social living, individual groups are creating new forms of housing.

- Experimental living for older citizens has the potential to become part of the new norm.

Housing is about far more than shelter. For older individuals—those who may have reduced physical capacity, especially in later years—the impact of housing can become huge. Silke Gross, co-founder of Amaryllis, a multi-generational residential community in Germany, says: “If you are old, living on the third floor and don’t have an elevator, you are stuck in your home.” Hans-Werner Wahl, chair of the Department of Social and Environmental Gerontology at the University of Heidelberg, adds that, with respect to an individual’s own accommodation and its surrounding neighbourhood, “housing has a lot to do with maintaining independence and autonomy ”.

Accommodating choices

The dominant accommodation options for older citizens, however, pose challenges for maintaining this autonomy. The problem is that, in the words of one recent study, as both physical and psychological capacity declines with age, the four walls of a house or apartment can become a cage.1 As a result, “older adults, realising that they may face many years with some level of physical or even mental impairment, see that they have to prepare for another kind of living arrangement,” Professor Wahl says.

Until recently, the only practical option involved nursing or long-term care homes. Accordingly, small numbers of those aged over 65—about 5% of the population in Germany and 6% in France—live in these institutions.2 The need for a middle ground, which balances autonomy with support, is obvious. Institutional solutions, such as protected or sheltered housing or assisted living, have appeared, offering tenants the ability to live in private accommodation with speedy access to medical and other types of assistance.

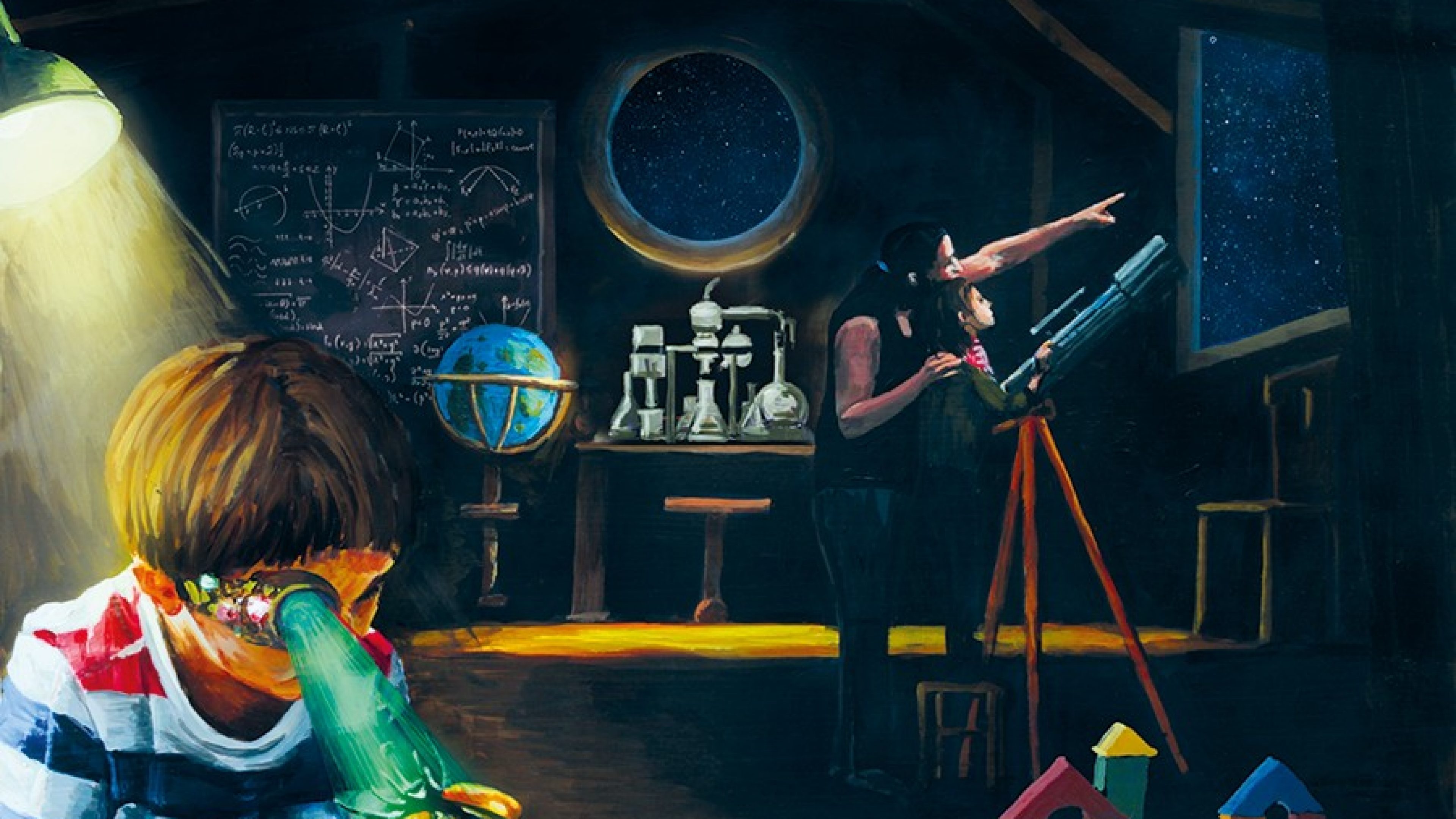

More interesting is the growth of new forms of housing, created, or co-created, by older citizens themselves to meet their own needs.

Making a house a home

La Maison des Babayagas in Montreuil, near Paris, is an example of this new type of co-housing for the elderly. The apartment building houses 21 older women, and although legally it is a public-private partnership between the residents and the local government, it is essentially run by the women as a co-operative.

The first aim of the co-operative, notes Iro Bardis, president of the residents’ association, is to provide accommodation specifically for low-income women living alone. According to Ms Bardis, females as a group tend to live longer than men and, on average in France, have lower savings and pensions because of time spent out of paid employment, often to look after the family.

The house also harnesses opportunities created by a community of women living under the same roof. Ms Bardis says that the residents reject the stereotype that “to be old means doing nothing. The idea behind the house is to be autonomous, to be active citizens in the local community, to take part in democracy, to engage with current ideas. Every one of us should pursue autonomy and healthy lives because, we believe, our commitment to independence will benefit everyone around us in society!”

All ages, all types

The concept of inter-generational living is showcased in Bonn, Germany. Amaryllis is a collection of flats and buildings designed to house individuals and families of various ages who are seeking to create a community, with public spaces laid out to increase the likelihood of meeting with others. “This enhances autonomy, particularly for older residents, because it is easier to meet neighbours, to be in contact, to feel safe. Communication lines build up. You know if you don’t come out of your flat for several days, friends will check on you”, says Ms Gross.

The interaction of people from multiple generations also lets older residents take on a valuable social role rather than simply having their own needs met. They may, for example, provide babysitting services for younger couples.

Moreover, Amaryllis is structured to encourage everyone to take an active role in decision-making and community affairs. “It is important that we are a housing co-operative,” Ms Gross explains. “Everyone is a tenant, and each member has one vote. This has forced us to discuss and do things together. This kind of project works well if people are willing to engage—to the extent they can—and not to be simply consumers.”

Europe’s new housing landscape

The trend towards new forms of accommodation for older people is still in its infancy. Nonetheless, Professor Wahl believes that these types of accommodation options are growing. Similarly, both Ms Bardis and Ms Gross report a steady stream of domestic and foreign visitors from Europe and even further afield, who are interested in learning from their efforts in order to set up similar arrangements elsewhere.

The precise nature of what is called for and what is on offer tends to differ markedly across Europe for both cultural and legal reasons. Professor Wahl notes that the cultural importance of autonomy in Scandinavian countries has led to political support for investment in new types of housing, but this has been lacking in other parts of Europe.

Experimentation is also continuing apace. The French government, for example, is seeking to promote inter-generational living through schemes for older people to rent spare rooms to younger ones..

This is a time of widespread experimentation rather than wholesale change in Europe. Given the region’s growing number of older people and their general unwillingness to accept institutionalisation, it is almost certain that the number and scope of accommodation options will multiply, but it is as yet unclear which type of housing—if any—will become dominant.

Source:

1 Frank Schulz-Nieswandt et al., Neue Wohnformen im Alter: Wohngemeinschaften und Mehrgenerationenhäuser, 2012. Translation by the author.

2 For France: Anne Labit, “Habiter et Vieillir en Citoyens Actifs : Regards croisés France-Suède,” Retraite et société, 2013; for Germany: estimate by Professor Wahl.

Written by