Some companies live longer than others. McKinsey partner Claudio Feser knows what these companies do better.

Mr Feser, you examined company life cycles for your book.* How long do companies last, on average?

Much less than people generally think. Half of all publicly listed companies disappear within a decade. Only one in seven makes it to 30, and only one in 20 sees its 50th anniversary. As with people, most companies follow a natural life cycle of birth, growth, maturity and death.Unlike with people, however, not every company experiences “death”.

Some have been around for hundreds of years, as we showed in an article on the Methuselahs of the corporate world. What do these companies do better than others?

First, you have to know why companies do not last long. Markets are dynamic, but companies are not. The markets redeploy around 20 to 25% of their capital every year in the search for more attractive returns around the world and in different industries. By contrast, companies redeploy only 2% to 6% of their capital each year.

Why is that?

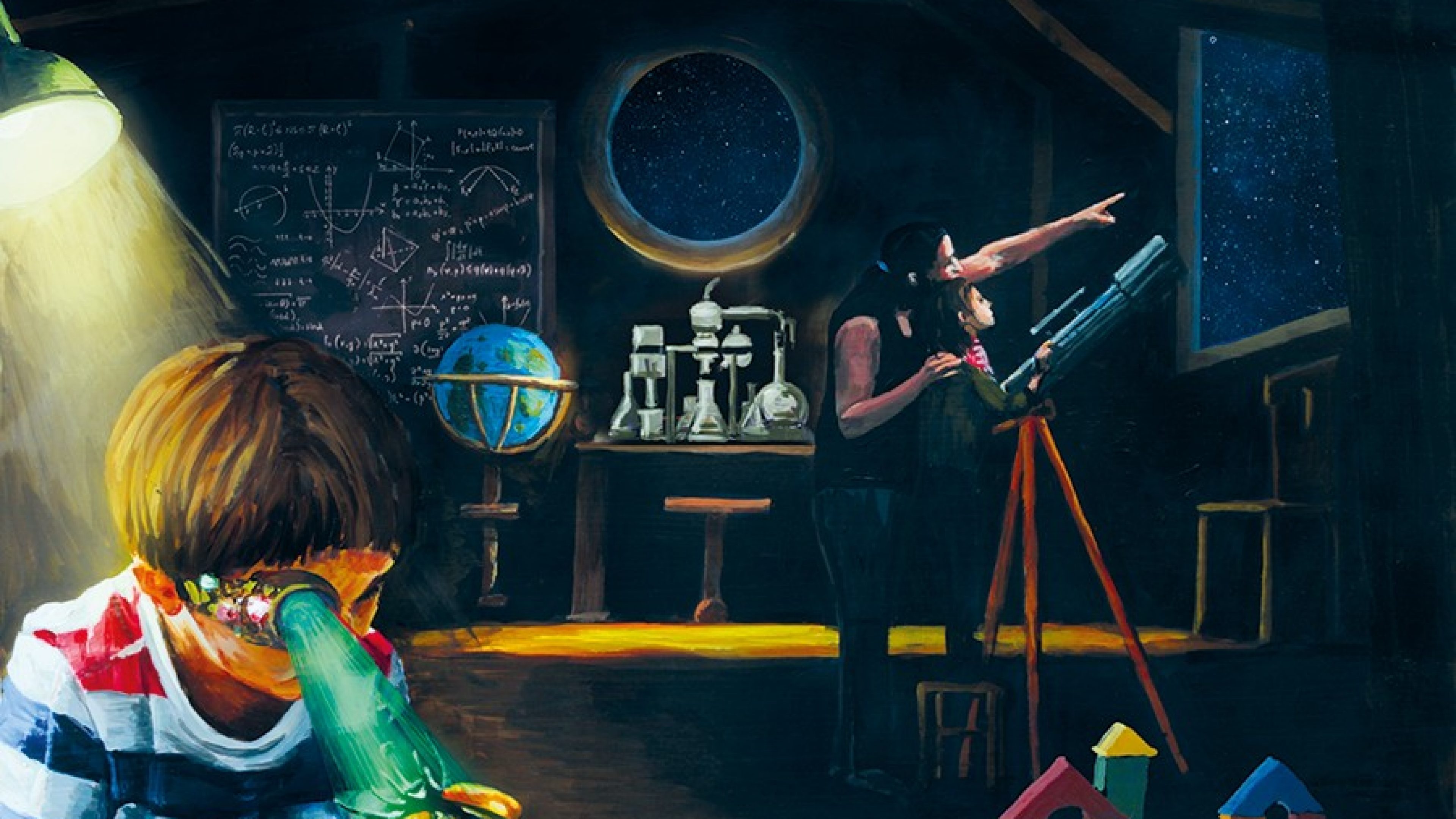

Companies are often, at least in the short term, bound to certain regions and certain markets. To put it simply, their budget is often simply the previous year’s budget plus a couple percent. Companies that have been around for a long time tend to be more dynamic. They question themselves, they experiment, they constantly develop new products, processes and business methods. They are therefore able to adapt to changing markets and environments and extend their life expectancy. I call such companies serial innovators.

Could you name two or three companies that you think do this particularly well?

It is difficult to single out particular companies because the specific approaches for continuous innovation are so varied. But if I had to name three companies, they would be Pixar, Apple and Novartis. They manage to constantly reinvent themselves and not only expand existing markets, but create entirely new ones.

Other companies do not do this. Why not?

Like biological organisms, companies age. Their “metabolism” slows down and they become more sluggish. Behavioural psychology refers to this as “rigidity”, which is another way of saying they become more cumbersome. A company’s processes become more bureaucratic and its corporate culture becomes inflexible to change.

Why does this occur?

Based on their experiences, people develop patterns of thinking that make them act in a biased manner. Psychologists call this “cognitive bias”. A study by McKinsey, for example, showed that managers often give disproportionate weight to potential losses compared to potential gains. For example, they hesitate to make investments if these have to be recognised in the income statement as an expense. Such thinking can sometimes prevent managers from identifying important market or technological changes and seizing worthwhile opportunities.

Could you provide a concrete example of this?

One prominent example is Bethlehem Steel, which was one of the largest companies in the US in the 1950s. Its management, perhaps precisely because it had been very successful for so long, did not see the ground-breaking developments that were occurring, such as the trend towards mid- and low-rise buildings – and thus lighter steel construction – as well as the emergence of a new production method called continuous casting. The company found itself with products that were no longer needed and a cost structure that was no longer competitive. After being in existence for 140 years, Bethlehem Steel filed for bankruptcy in 2003.

What can companies do to combat such sclerotic mentalities?

You have to act on both an individual level and on an organisational level. On the individual level, serial innovators are typically run by a diverse set of people. Gender diversity is, of course, one issue. It is also important for managers to have as diverse a range of experience as possible. Beyond this, the team dynamic has to work. Healthy debates are crucial for the survival of companies, and team members must be able to build on the viewpoints of others.

And on the organisational level?

Serial innovators tend to be organised in smaller, relatively independent units. They experiment more in order to be able to establish new skills and capabilities more quickly than the competition. Most importantly, they tend to have a corporate culture that not only rewards performance, but one that also calls for opposing points of view and debates. In this way, serial innovators constantly challenge themselves to become better.

How important is a critical external point of view?

Having an external point of view provides exposure to other ways of thinking and experiences. A large Swiss corporation is a good example of this approach. Each year it invites four or five external experts to a two-day management workshop and asks them to challenge the group’s strategy and uncover its weaknesses. This is not pleasant for managers, but it is a highly effective method for obtaining new perspectives on a problem. Sometimes this sort of external challenge is the only way to provide the company’s senior management with new perspectives and fresh ideas, especially at very hierarchical and bureaucratic organisations.

In an article, we showed that Millennials have a new conception of work. In particular, they want their work to have a purpose and they want to change the world. What do you think: Will this development extend or shorten the lives of companies?

The desire to do make a contribution to something bigger than themselves may be expressed more loudly by Millennials than previous generations, but this desire is not limited to younger generations. Instead, I would say that the quest for meaning in life is a basic human characteristic. But because Millennials are expressing this need to a greater extent, more companies may be reflecting on their own role in business and society. And this process of reflection and the measures that are taken may actually make a company more resilient and able to adapt.

*Serial Innovators: Firms That Change the World, Wiley 2011.

Claudio Feser, 54, is a senior partner and member of the global Shareholders Council (board of directors) at McKinsey. He led the company’s Swiss office from 2005 to 2010. During his career, he has advised CEOs at some of the world’s largest companies.