Although smartphones are making us more independent, they are also seducing us to permanent distraction and constant availability. Is the emerging generation of “digital natives” able to benefit from the Internet in a self-determined manner or is it controlled by its devices? Scientists are divided.

Never before has digital technology been so omnipresent as today: eleven to 15-year-olds in Switzerland spend four-and-a-half hours each day in front of a screen (be this a computer, smartphone or TV) and as much as 7.4 hours at the weekend. This is one of the findings of the highly regarded HBSC study sponsored by the World Health Organisation. In Germany nine out of ten 13 to 14-year-olds already have mobile Internet access. And in France one in three 18 to 24-year-olds first of all reaches for their smartphone after waking up.

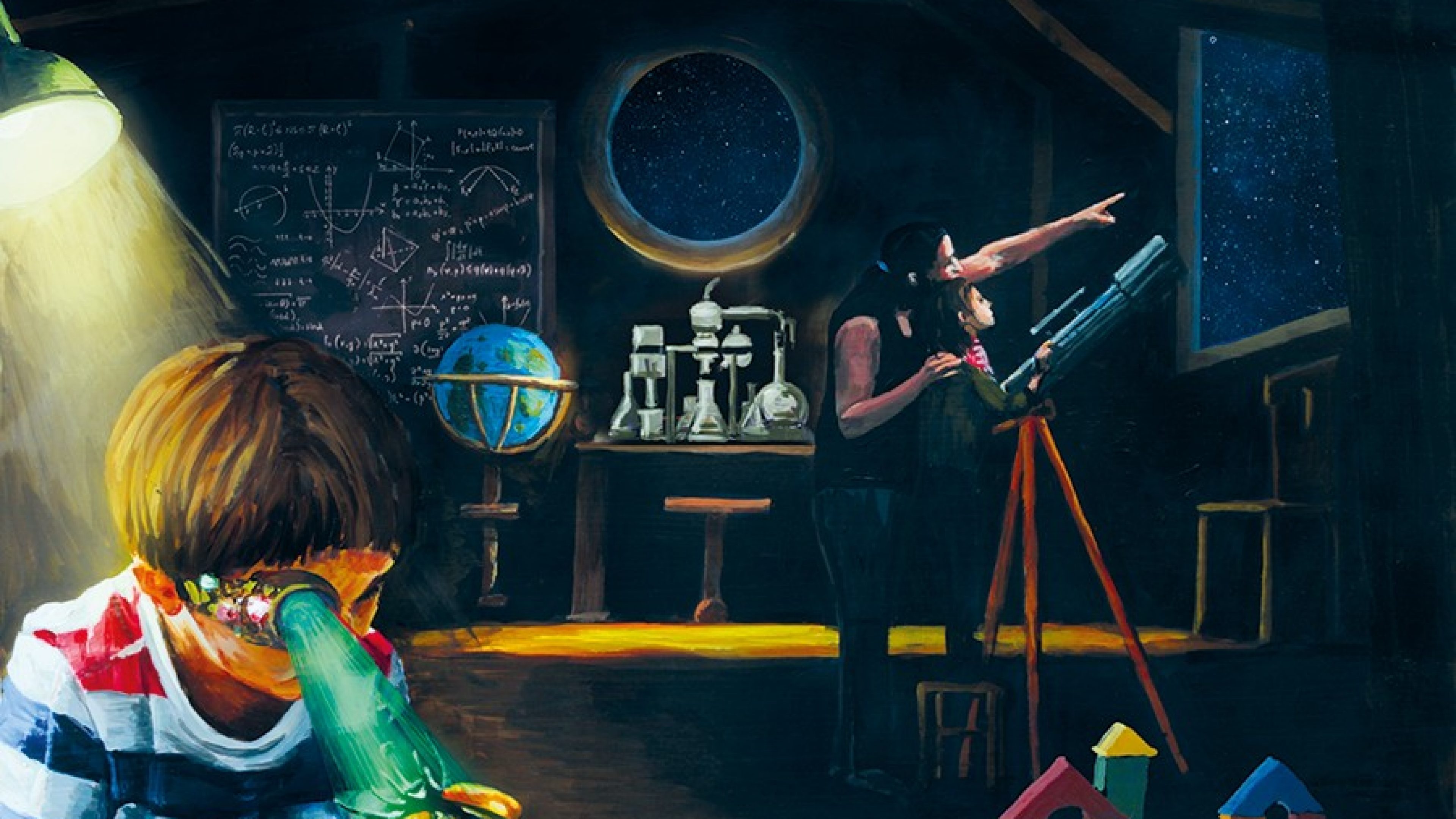

What does this technology push mean for young people? Is it leading to the dependence and control of the “digital natives” born after 1980? Or is a generation growing up that is extremely self-determined, that is making use of its digital freedoms to communicate creatively via a wide range of channels and become better informed about the world than any preceding generation?

Scientists are divided and – to exaggerate somewhat – divided into pessimists and optimists:

The pessimitsts

Sherry Turkle is no scientist who could be accused of technophobia. She is a professor teaching at the renowned MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) where the W3C consortium defining the standards in the World Wide Web is based. Nevertheless, the sociologist examining the relationship between man and computer is alarmed. “We are in a state of alertness disorientation,” she warns. “Our gadgets are permanently kept on and we are continuously dividing our attention between the people we can contact by mobile phone and those with whom we are physically present at that moment.” Moments of silence have become a rarity and young people in particular are consequently losing the ability to be alone. And yet it is only through being alone that we can find ourselves: “A generation that perceives being alone as loneliness lacks autonomy.”

Manfred Spitzer is even more critical in his assessment of this lack of autonomy and the control exerted by the permanent use of social networks, by the pressure to be constantly available and by hours spent surfing. The German psychiatrist and brain researcher is convinced that this leads not only to addiction but also to depression and anxiety. Spitzer even suspects the risk of “digital dementia” among digital natives: “The brain can be compared with a muscle: whenever it is used it increases in size,” he writes. “If we therefore outsource mental activities in increasing quantities to digital media, this has a negative impact on the structure of our brain, on our brain formation.”

The optimists

Meanwhile, other scientists are warning against alarmism and advocating a different perspective. “We have to be careful not to get caught in the trap of nostalgia: everything was not better before the smartphone. It was just different,” says Swiss educationalist and author Philippe Wampfler (Generation Social Media). He can also see the problematic aspects of excessive media usage that affect children and young people more quickly today than used to be the case. “However, there are also tools such as YouTube and Twitter that give a great deal of independence and facilitate networking through the exchange of information”, says Wampfler, and adds: “If I wish to ensure that the freer and faster flow of information through the Internet marks progress, I need to remain an optimist.”

American education specialist and writer Anya Kamenetz (The Art of Screen Time) also underlines the opportunities arising from digitalisation. In an original approach, she compares them with food allergies: “For most children, peanuts are simply peanuts.” Only a small number react allergically to them.

And in fact for most of them there appears to be no risk of becoming controlled through digital consumption. For one thing, young people are able to learn how to handle the new media in a self-determined, creative and responsible manner. At the same time, the German “Child media study” that has just been published also serves to allay fears: children still prefer to be in direct physical contact with their friends and they enjoy reading and playing football just as much as using their smartphones.

Self-determination in all areas of life

Optimists such as Kamenetz have absolutely no doubt that mobile devices offer the vast majority of digital natives more self-determination in all kinds of areas of life. Children are permanently reachable for their parents via mobile in the event of an emergency, thereby enabling them to travel alone at an early age. This fosters their sense of responsibility and independence. Furthermore, smartphones not only facilitate social networking but also the networking of interests and therefore also political co- and self-determination. And thanks to digitalisation and the gig economy, the labour market offers the option of solo self-employment and thus more independence, flexibility and self-determination.

A generational question?

The experts agree on one issue: the effects of digital consumption and the potential risk of becoming controlled cannot be confined to the young generation. As MIT professor Sherry Turkle explains, “Everyone is distracted, whatever their age: students send text messages during lectures, parents send text messages over dinner with the family or when they’re with the children in the park.” According to the researcher, the mere presence of a smartphone alters the atmosphere.

Probably only long-term research will be able to offer conclusive answers about the effects and potential collateral impact of online everyday life on digital natives. But it is already clear today that we are by no means helplessly at the mercy of the lures of the digital world. We can determine our own lives. That doesn't mean no longer using smartphones but using them more smartly.