Nowadays, retirement provisions enable us to lead a financially self-determined life in retirement. But how did this system of old-age insurance system actually come into being? Historian Matthieu Leimgruber discusses the history of pension systems and the important contribution they make to a functioning society.

The idea of retiring with a pension is surprisingly new, having only became established during the 20th century. How did people prepare for their old age before that?

They didn’t. The idea of retirement – viewed as a period of a person’s life – did not exist for thousands of years. You simply worked until you died, although life expectancy was also much lower. The elderly received support from family associations or, if necessary, from poor houses.

What caused the rethink of the status quo?

Society underwent major changes as a result of industrialisation during the 19th century. People moved to the cities, where they worked in the factories and traditional family bonds began to break down. Life expectancy rose dramatically and at the same time, the risk of poverty in old age increased significantly. This is how the debate began on “social issues”, that is to say absences from work due to illness or disability, unemployment, and the challenge of enabling older people to live a dignified life when they are no longer able to work.

When did the first pension insurance schemes come into being?

The first pension schemes for certain civil servants and military personnel were introduced as early as the 18th century, while life insurance and occupational pension schemes began to proliferate over the course of the 19th century. However, only a very limited group of people benefited from these.

And who invented universal retirement provisions?

Under Chancellor Otto von Bismarck, the German Reichstag enacted the first statutory pension scheme in 1889. A historic act, but above all a sedative for the stronger working class.

How do you mean a “sedative”?

At the time, it wasn’t the case that these retirement provisions would be enough to live off. Pensions were not only small, but were initially only paid once people turned 70. However, average life expectancy was only 55 and even less for lower-income workers, meaning very few people benefited from pension payments.

When did a functioning retirement pension scheme come into being?

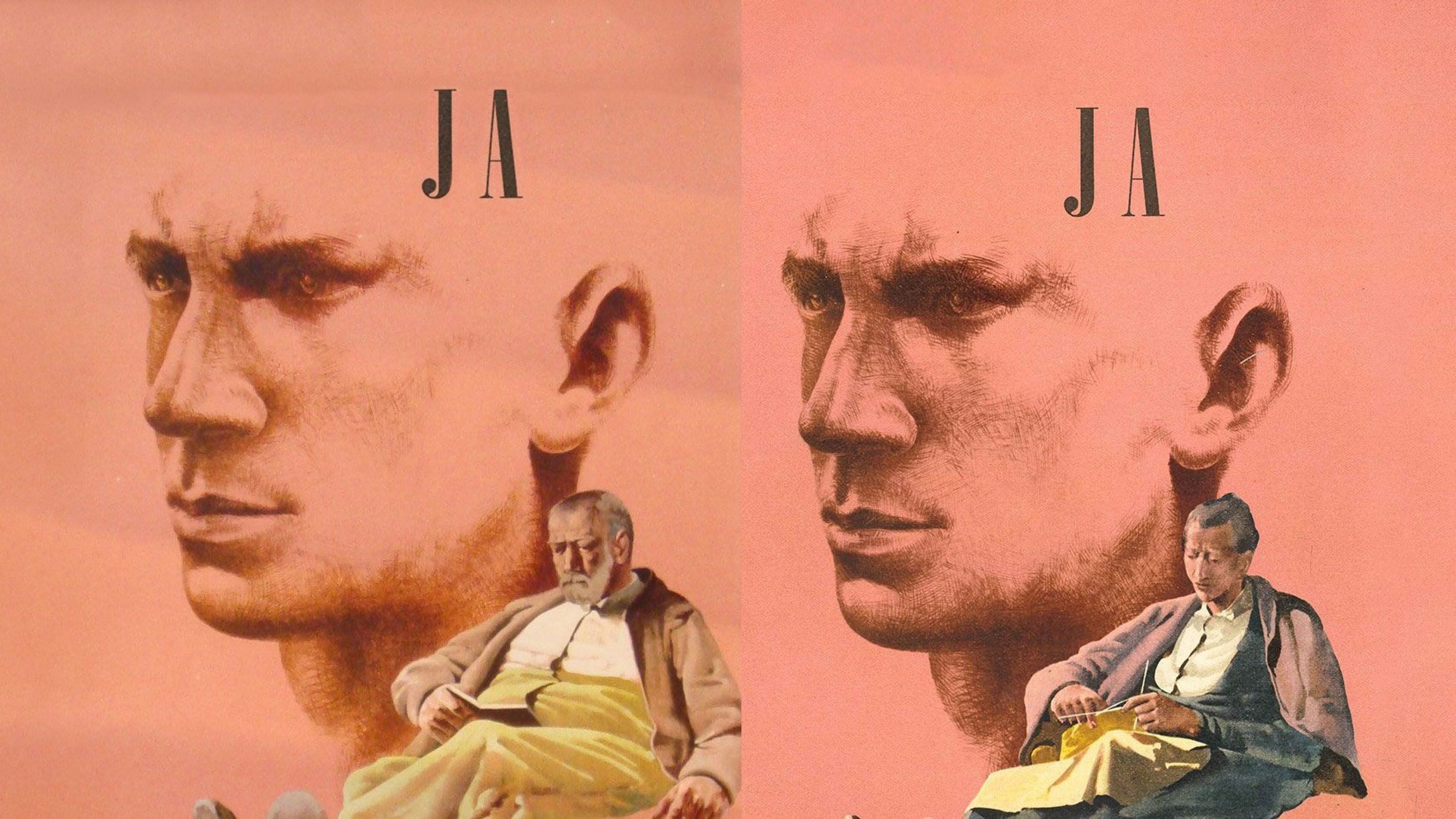

During the interwar period, many industrialised countries – such as France in 1930 and the US in 1935 – introduced old-age insurance. However, these were only really extended to the entire population in the immediate post-war period. The introduction of AHV/AVS retirement and survivors’ benefits in Switzerland in 1948 is an example of this trend. The introduction of all these schemes was immediately followed by heated debate about the income received by older people.

What triggered this debate?

The world had changed radically. Various economic crises and two world wars were followed by a sustained economic boom, which opened up completely new perspectives when it came to retirement provisions. Now the question arose of how the previous minimum basic insurance could be expanded to include an “old-age salary” to enable pensioners to maintain their former standard of living. Not only did the gross pension amount need to be increased, but pensions had to be regularly indexed – similar to what had been done in Germany since 1957 – in order to adjust them in line with changes in the cost of living.

Benefits were expanded and the systems as we know them today were finally implemented in the 1960s and 1970s, with countries adopting very different solutions. What are the main differences?

In addition to basic insurance provided by the state, many countries also had other forms of retirement provisions, such as occupational pension funds. Different financing methods and the division of responsibilities between the state and employee benefits institutions have led to major differences between pension systems around the world. A prime example is France, where the “special schemes” for civil servants and employees in the public sector and the pension funds for executives and employees in the private sector adopted the “pay-as-you-go” system of basic state insurance. This approach is typical for countries in which employee benefits institutions have historically played a minor role or were weakened by wars and crises in the first half of the 20th century.

Other countries rely more on private initiatives and individual decisions, including the Anglo-Saxon and Scandinavian countries, but also Switzerland.

That’s true. Here, the pay-as-you-go system only applies to the state pension, referred to in Switzerland as the “first pillar”. These countries also rely on the fully funded system and the performance of occupational provisions and individual savings. A special feature of the Swiss approach is that, unlike, for example, in the US or the UK, where occupational provisions remain voluntary to this day, occupational provisions have been mandatory since 1982. At the heart of this “second pillar” are pension funds managed by public and private employers or life insurance companies. The latter have played a major role in shaping retirement provisions.

What was the significance of Schweizerische Rentenanstalt, founded in 1857, known as Swiss Life since 2002?

It played a key role on several levels. Swiss Life was the first company in Switzerland to offer pension insurance, which contributed towards the establishment of life and pension insurance as a means of financial security. At the end of the 19th century, it also developed the first life insurance policy for the general public, also known as “public insurance”. In doing so, it helped in the fight against poverty in old age, albeit modestly, since the sums insured were very low at the time.

Nevertheless, there was a huge demand for this: of the approximately 800 000 life insurance policies taken out in Switzerland in 1925, just under half were public insurance. It is also noteworthy that not only was this department managed by the company secretary Mathilde Pfenninger, but all 100 employees were women. What is the reason for this?

Women simply had better relationships with customers, especially their female customers. In working-class families at the time, women usually managed the family finances and they were also at home when the representatives from the insurance companies knocked on the door to sell insurance.

Was the former Schweizerische Rentenanstalt also involved in developing the system for AHV/AVS?

Yes. Since in the first half of the 20th century it dominated the market for pension funds – that is to say, group life insurance for private employers – it played a key role in this. Politically the company was very close to the then ruling party of the FDP and, together with the other major life insurers, regularly took part in the debates on the AHV/AVS. With its organisational and actuarial expertise, Schweizerische Rentenanstalt played a key role in shaping the idea of a tripartite pension system.

Has the idea of retirement provisions gained global acceptance today?

No. It remains a major challenge. Fewer than twenty percent of older people worldwide enjoy a retirement pension that is enough for them to live off. Although countries like China and India are now also developing their pension systems, the prospect of most older people receiving pensions totalling 60 to 70% of their final salaries remains a long way off.

In view of rising life expectancy and the simultaneous fall in birth rates, retirement provisions are becoming increasingly difficult to finance. Today, around 20% of Europe’s population is already over the age of 65, and this figure is rising.

We are now actually in the third phase in the history of retirement provisions. There are currently heated debates on reforming pensions. It is primarily a question of maintaining the system and the matter of how much should be saved in future by the general public and how much by individuals.

Is there a threat that the idea of retirees receiving a pension that is enough to life off will become a brief chapter in world history?

No, I don’t think that’s the case. Retirement provisions are one of mankind’s great achievements. The alternative would be massive poverty in old age, as history has shown. Countries that have tried to fully privatise pension systems – such as Chile under Pinochet – have failed. The only solution is to socialise the risks of old age.

© Portrait Photo: Virginie Otth

Matthieu Leimgruber

Matthieu Leimgruber (51) is Professor of 19th and 20th Century History at the University of Zurich. He conducts research on the history of social security and retirement provisions and wrote the standard work “Solidarity without the State?” (Cambridge University Press). More information: www.historyofsocialsecurity.ch