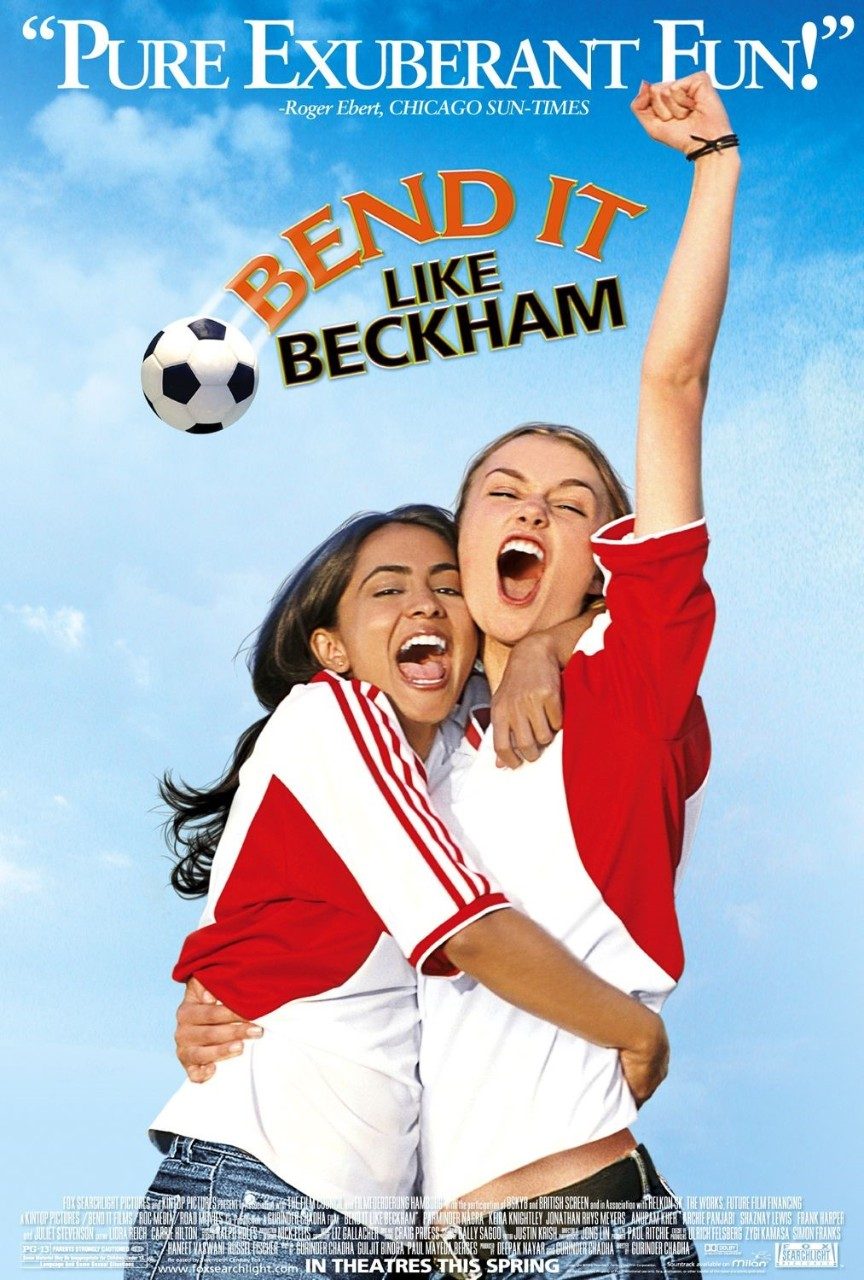

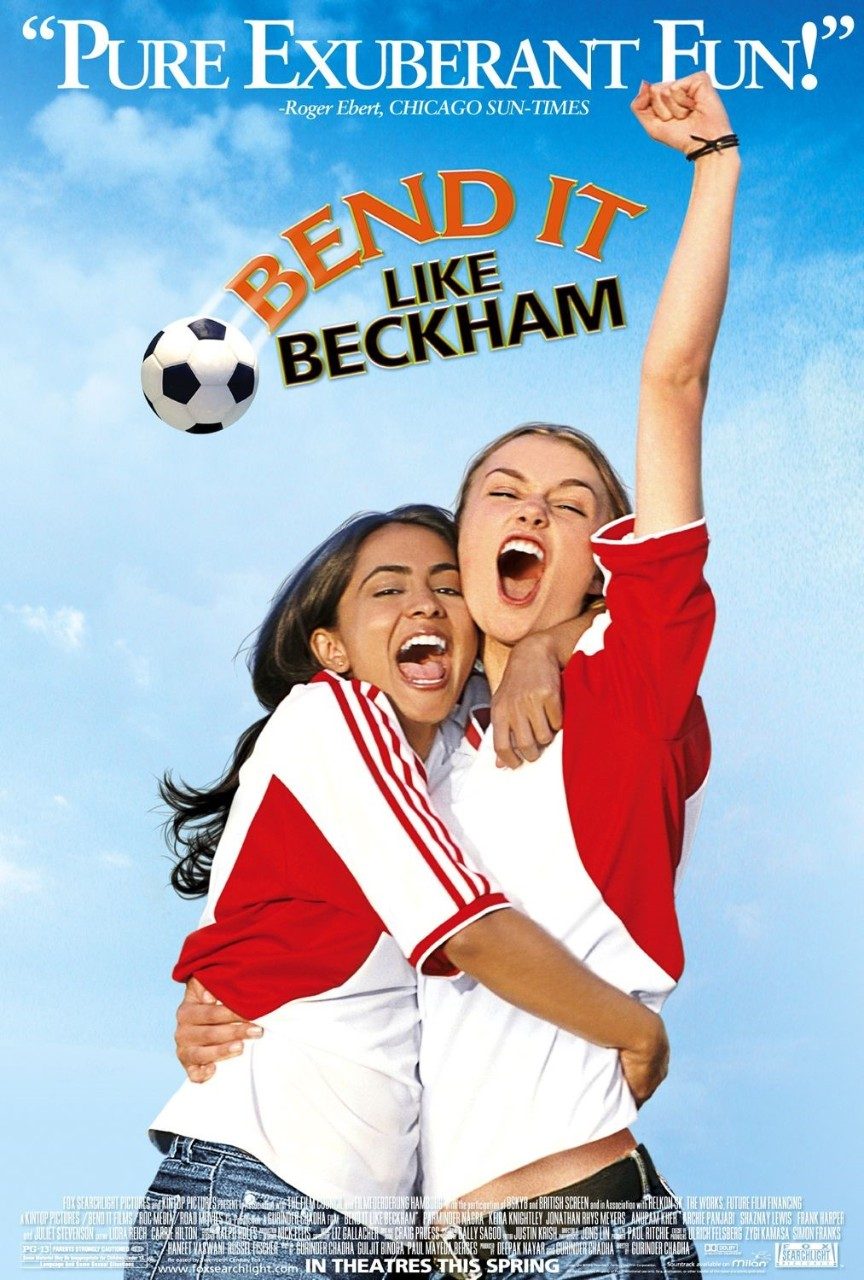

Permi Jhooti is a pioneer of women’s football and a role model for millions of girls. The hit film “Bend It Like Beckham” tells the story of the woman who now lives as an artist in Switzerland. A discussion of the struggle for a self-determined life.

"Bend It Like Beckham” exploded on the scene in 2002, bringing women’s football broad public attention for the first time. How did your story make it to the screen?

In 2000 I became the first female pro footballer with Asian roots when I signed with London’s Fulham Club. When British director Gurinder Chadha, who also has Indian roots, heard my story, she decided to make it into a movie. She used football to make some pretty elementary points about the first generation of Indian immigrants in England and their conflict with their children.

What was the nature of that conflict?

For one thing, the family values those immigrants passed down were traditional and conservative. We women could look forward to an arranged marriage and a role as mother. For another, our parents saw education as key to a proper future. Although they were very intelligent, my parents were obliged to clean toilets for a living. They wanted us to study hard and become doctors, lawyers and teachers. But our generation wanted to do something beyond such expectations, both in our personal and in our professional lives, whether as footballers or – as in the case of Gurinder Chadha – as film directors.

You were originally to have played the lead. Why did you pull out?

I didn’t like the final screenplay. Most of the facts were correct – the problems with my parents, the forced engagement to an Indian, the relationship with my trainer – all of that actually happened. But for me my life was much more profound, much more complex than the film makes it out to be. I just couldn’t play myself the way the screenplay was written.

What reconciled you to the film?

Audience reaction. Lots of people told me how much the film had inspired them to be themselves. That’s when I realised that it was being understood, despite the simplification of reality. It sparks something in people, it gives them courage. And that was the most important thing for me.

What gave you the courage to fight against convention?

What you mainly need is trust. I had a wonderful teacher in primary school, who listened to me and was there for me when I got on people’s nerves and made trouble. She said, "You’re special. I may not know what it is, but you will be able to do something unusual.” I have never forgotten that sentence. And I have been trying to prove her right to this day. Later on, too, I kept meeting people who believed in me without pushing me in one direction or another. People who gave me the feeling I could achieve my goals.

Not only did you become a footballer against the wishes of your parents, you also refused to enter into an arranged marriage. How did they react?

That was very hard for them. My mother in particular had a very violent reaction. She said, “I wish you were dead. You are a disgrace to our family.” It would have been normal for me to be disowned by my family at that point, but my father died just before he could inform me of the decision. What I understand today is that they also wanted to protect me from the outside world, from the racism they had experienced themselves.

Have you made your peace since?

Yes. After my father’s death friends and family gathered at our house to mourn. All of them Indians, including my aunts, who had disowned their own daughters for refusing arranged marriages. Then the doorbell rang, and my white boyfriend at the time, Ian, was standing there. And what did my mother do? She threw herself on him, embraced him and said, “Look everyone, this is my son.” She didn’t apologise, she didn’t explain, as if it was the most natural thing in the world. I couldn’t have been prouder of her.

Is it lonely going your own way?

On the contrary, I felt much more alone before I took my own path. I was fighting my thoughts, hiding my feelings and afraid to break my family’s rules. I could feel people looking at me and talking about me. But if you lead an honest life, then your conscience is clean. You’re free, and invulnerable to attack. Independence like that makes you strong, and you really get the best out of yourself. Self-determination, in other words, does not mean less quality of life, it means more.

After your career as a footballer you worked in Basel as a successful IT specialist in cardiac research. You gave that up five years ago to become a renowned photographic artist. Is the life of an artist the highest form of self-determination?

No. What matters in life is honesty and passion, whatever your profession. I was separating from my husband, Ian, at the time and looking for a new beginning. Although I liked my job, I wondered whether it was really what I had wanted to do when I was young. So I bought a camera and put my programmer’s know-how at the service of art. Viewed objectively it made no sense, since I had zero experience with art and initially I basically earned nothing with my pictures and videos. But I had followed my heart, and was totally at peace with myself.

Aren’t you afraid of failing?

Of course I am. My friends think I don’t know the meaning of fear, but that’s utter rubbish. I am in fact enormously afraid of failing. But failing would mean not taking a risk. I'm terrified of failing to live.

Back to football. Following your retirement from professional sports you travelled halfway around the world as a FIFA ambassador, building up women’s clubs and leagues. Are you disappointed that women’s football has never had the same publicity as men’s, despite the boom?

Maybe women’s football will make it there in ten years. They used to say tennis was a men’s sport as well, but women and men are winning the same prize money at the big tournaments these days. For me personally though it was never about spectator numbers and money.

What was it about then?

What I was mainly fighting for was a woman’s right to play football. And today, across the world, there are over three hundred million amateur women enjoying the sport. And what’s more, I have learned that when women are allowed to play football, their position in society improves too.Do you still play football yourself?

Yes, when I am in London I meet my old gang in the park. As soon as I have a ball at my feet I become a different person. My whole posture changes, as if I were dancing. I love the feeling.

Artist

Permi Jhooti

Pioneer of women’s football

Permi Jhooti (48) was the first Asian woman pro footballer, once playing for Millwall, Chelsea and the Fulham Ladies. Her life served as the inspiration for the film “Bend It Like Beckham”. British-born of Indian parents, Jhooti has lived in Basel since 2005, having worked at the university there as an IT specialist in cardiac research. For the past five years she has been pursuing a successful career as an artist. Her photographs and videos combine art, science and technology.

"Bend It Like Beckham" (2002) is a comedy by Gurinder Chadha, a UK citizen of Indian provenance. It was a surprise hit worldwide, garnering over 30 million viewers, won the Audience Award at the Locarno Festival, among other prizes, and is used for educational purposes in schools. The comedy is one of the most successful UK productions of all times.

Swiss Life supports the Swiss Football Association

Swiss Life has been a partner of the Swiss Football Association since 2004 and also supports women’s and young people’s involvement in the sport. From 18 to 30 July 2018 the UEFA Women’s Under-19 Championship will be held in Switzerland.