- Maintaining independence later in life is key to an overwhelming 91% of respondents surveyed by the Economist Intelligence Unit.

- The European Commission predicts that over-65s will make up almost 30% of EU citizens by 2060. According to Alfonso Sousa-Poza, a German professor of economics, happiness rebounds after middle age and remains pretty much constant right up until the end of life.

- The lens of self-determination offers a broader view of fulfilment, weaving together autonomy, competence and social relatedness through each stage of life.

- Approaches to active ageing recognise that people can remain healthy and socially engaged members of society as they grow older, finding more fulfilment in their jobs and more independence in their lives.

Human beings have long tried to define what it means to live a good life. Social scientists, psychologists and economists continue to wrestle with this question today, and as longevity increases to record levels in Europe, many are asking: how does our ability to lead a self-determined life change as we grow older?

The concept of self-determination maintains that traits such as motivation, personality and well-being form underlying elements needed in order to achieve fulfilling goals. Autonomy, competence and social relatedness are three prerequisites that make the concept of self-determination a reality in people’s lives. Increasing longevity changes the ways in which ageing needs to be considered, meaning that older people must find new ways to adapt and develop in their later years.

Ageing is not what it used to be

The layperson assumes that most people should be concerned about the prospect of ageing. Declining physical reserves, aching joints, reduced income and fewer job opportunities are just some of the unattractive characteristics frequently associated with growing older.

This image, however, is increasingly outdated. What we think of as old has changed over time, and it will continue to change in the future as people live longer, healthier lives according to Sergei Scherbov, deputy director of the world population programme at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), a research organisation based in Austria.

Indeed, according to the IIASA, “old age” today does not begin until someone reaches the age of 74. This calculation is based on the number of years left to live (15 or less), rather than the number of years already lived.

Overall life expectancy is rising across Europe. According to the OECD, it is increasing by three months each year, and by 2040 it is expected to reach 90 years. The European Commission predicts that over-65s will make up almost 30% of EU citizens by 2060.

What hope does this rising number of older people have for a good life? One dimension that gerontologists and other researchers look at is the so-called health expectancy, also referred to as healthy life years (HLY). This broadly refers to the number of years a person of a certain age will live without a disability. This varies across Europe: the average French person can expect nine healthy life years after the age of 65, compared with just seven in Germany.

Realising healthy lives

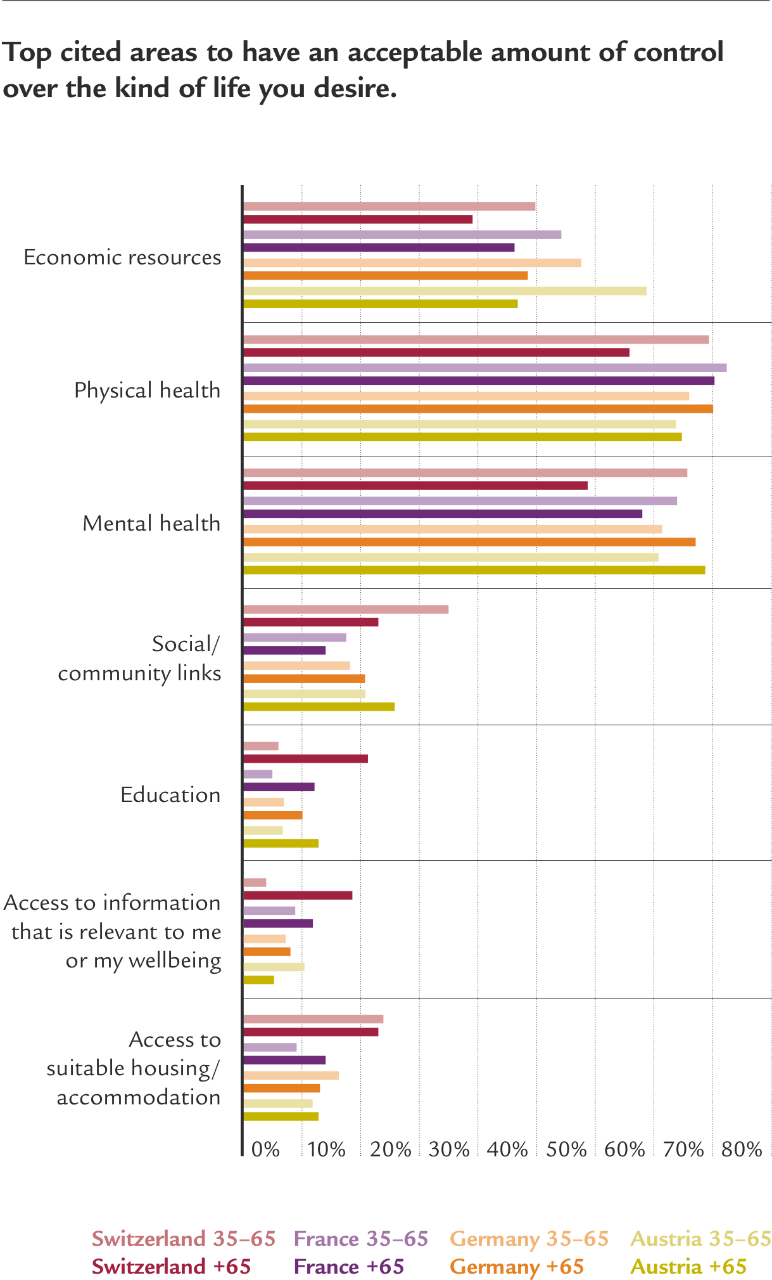

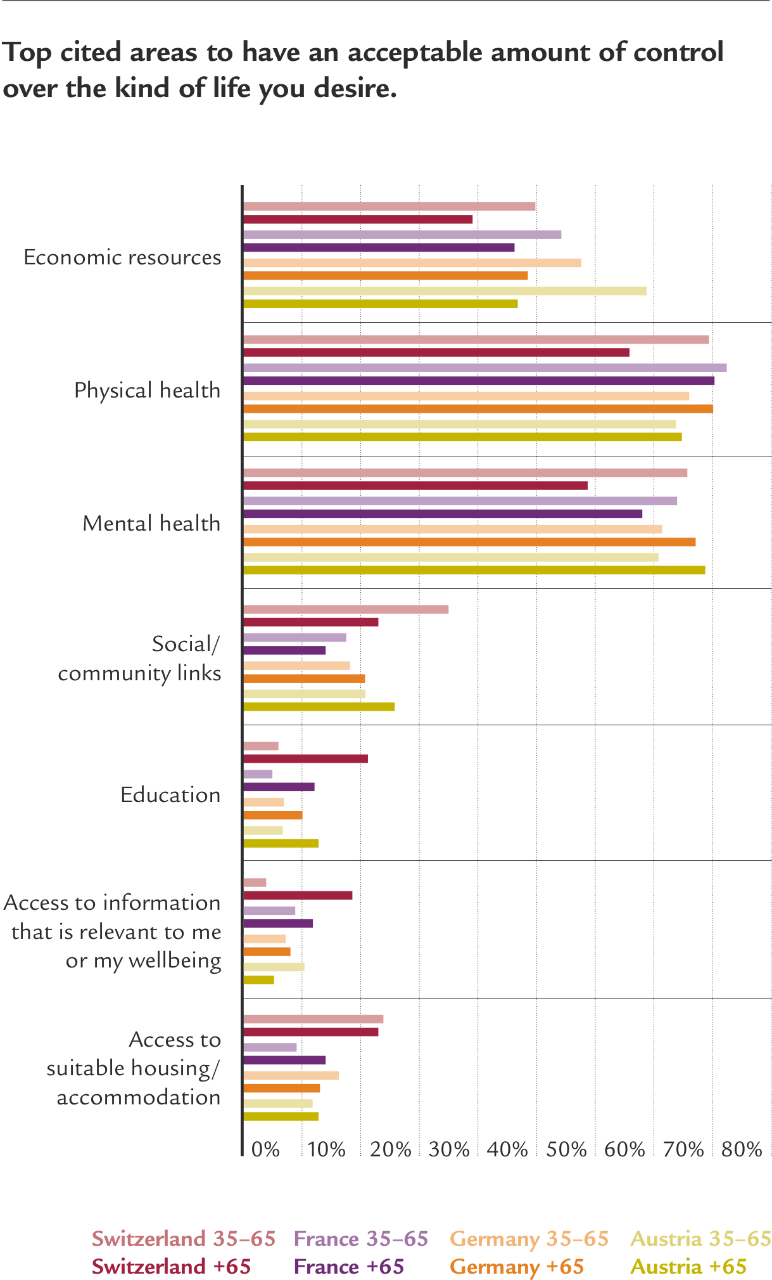

Health is only one measure of the quality of life, albeit a significant one. According to a recent EIU survey of over 1,200 people based in Germany, France, Austria and Switzerland, maintaining control of physical and mental health were overwhelmingly cited with regard to respondents’ most important priorities they needed to control in order to have the lives they desired. This applies equally to those over 65 and those aged 35-65.

The importance accorded to living a good, healthy life, in all its aspects, may seem apparent, but these results emphasise how far society has developed in its understanding of what is essential to living a good life. There is a conscious effort by many people today to sustain a healthy level of living, whether by doing more exercise or reducing stress levels. This is suggestive of the changing attitudes towards the responsibility of each individual in realising the type of life they desire.

Climbing Maslow’s pyramid

It is not sufficient to consider physical and mental well-being in isolation when assessing quality-of-life issues. Indeed, once basic needs have been met, a wider range of human goals must be addressed. These include meaningful social relationships and self-actualisation. In this, seniors in Switzerland stand out from their European peers. While still concerned about health and economic resources, these issues feature less prominently than in Germany, France and Austria. Moreover, the views of young and old respondents in Switzerland diverge, unlike those of their European peers. Broadly speaking, Switzerland has higher levels of GDP per capita and lower rates of chronic diseases, so it may make sense for these primary concerns to shift towards other areas of development and fulfilment.

According to the EIU survey, education (21%) and access to information (18%) are noticeably more important to Swiss respondents aged 65+ than to the other nationalities surveyed. Additionally, the value that Swiss respondents aged 35-65 (35%) place on social and community links highlights the importance of social connectedness. Those over 65 are less likely to cite this; it may be that many of the older generation already have relatively deep connections with their social community. This is highlighted by the Global Age Watch Index 2015, which indicates that nine out of ten of those over age 50 in Switzerland have a strong support network that they can turn to. Recognising this broader range of human needs can be complicated but no less vital to living fulfilling lives.

The defining importance of independence

The concept of self-determination holds that the more choices you are able to make and the more connected you feel to your community, the more fulfilled—and happier—you are likely to be. This is a useful measure as it focuses on independence, which is a critically important aspect of ageing. In the EIU survey, respondents overwhelmingly show that maintaining independence in later life is of major importance, at all ages.

Autonomy is integral to living a self-determined life, and the ability to make independent choices is embedded in its ethos. Indeed, an overwhelming majority (91%) of survey respondents state that independence is vitally important to them. The crucial importance of autonomy goes to the heart of a self-determined life, and people of all ages recognise the need to weave this into their lives.

How these elements influence personal well-being—an individual’s assessment of the quality of his or her life—is a benchmark by which to measure self-determination. Such evaluations are useful because they complement traditional “objective” measures and also take into account autonomy and independence, which are concerns at the very heart of ageing.

Paradoxes in happiness

Research suggests that life satisfaction increases from adolescence to middle adulthood, reaching a peak around the age of 40. People feel least happy in their 40s and early 50s, when many are prone to experiencing an ebb in their personal happiness—the so-called midlife crisis.

But in what is known as the “paradox of ageing”, it turns out that on average we get happier past midlife. Despite increasing physical challenges and often declining incomes, “after middle age, happiness rebounds and remains pretty much constant right up until nearly the end of life,” says Alfonso Sousa-Poza, professor of economics at the University of Hohenheim in Stuttgart and director of the Institute for Health Care & Public Management. This is remarkably consistent across countries and cultures.

A world of active ageing

Alan Walker, professor of social policy and social gerontology at the University of Sheffield and a leading expert on ageing, believes that the way we look at ageing is stuck in the past. In a recent speech he said that the longevity revolution is underpinned by improved health. Professor Walker envisages a world of “active ageing” in which we remain healthy and socially engaged members of society as we grow older, finding more fulfilment in our jobs and more independence in our daily lives.

In many European countries governments have been seeking new ways to encourage active ageing over the past ten years. The most recent UN Active Ageing Index highlights a range of improvements: France has recorded substantial increases in the employment of women aged 55-59 in the past decade, and Germany scores exceptionally highly for independent living and capacity for active ageing compared with the European average.

The foundations of a healthy and self-determined life clearly accrue over time — being physically active every day, maintaining a nutritious diet, consuming less alcohol and never smoking all help. Looking forward, older people need to make sure that they remain physically active, with strong levels of social connectedness. Working longer can also help to sustain a positive attitude towards life. “There is now ample evidence that seniors who remain active beyond the official retirement age are on average happier and healthier than those who don’t,” according to World Bank economists Wolfgang Fengler and Johannes Koettl.

Rewriting later life

But retirement—a key moment in the life journey of many older people—looms. How does retirement affect an individual’s capacity to live a self-determined life? “It improves it,” says Marcel Goldberg, professor of epidemiology at Paris Ouest Medical School, Versailles Saint Quentin University in France. “Our research suggests that people tend to be happier when they retire and achieve the same levels of health in retirement,” he says. “Retirees have more flexibility and freedom in their lives, fewer constraints, and keep up a rich and varied social life,.” Mr Goldberg adds.

The EIU survey highlights that what people most look forward to is being able to engage in their favourite leisure activities/pastimes, control their time and travel in their later years. Respondents in France look particularly forward to their ability to travel (64%) and the chance to engage with favourite pastimes (74%), while in Austria respondents most look forward to having control over their own time (63%).

The relationship between self-determination and well-being makes it necessary to uphold the three aspects—autonomy, competence and social connectedness—and to support them as they interweave. Although it is necessary that each fundamental is nurtured primarily by the individual, societies can play a part in championing self-determination as key to the well-being of the population as a whole.

Finally, it may be worth bearing in mind the advice of Jeanne Calment, a French supercentenarian who lived to a record 122 years: “Every age has its happiness and troubles.”

Download the article

Written by